Robinson Studies Genetic Variation and Autism

The diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) includes a wide range of behavioral and cognitive symptoms and outcomes. Researchers are learning more about this variability thanks to genetic data.

“ASDs are not one thing; they are many different things,” said Dr. Elise Robinson, at a recent NIMH Director’s Innovation Speaker Series lecture. “We’re starting to be able to use genetic data to understand variability within the diagnostic category of autism, as well as more broadly variability in how human beings think and act.”

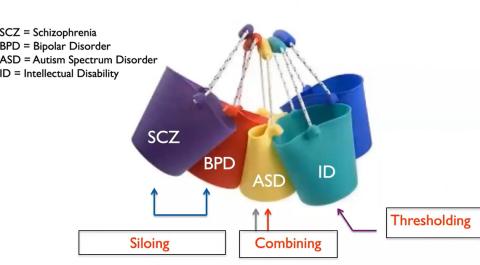

Robinson, assistant professor of epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and an institute member of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, framed the topic by depicting psychiatric disorder diagnoses as buckets. There can be overlap between genetic risk factors of different mental illnesses but also heterogeneity within a single illness.

Outcomes of an autism diagnosis can range from absence of speech to highly articulate, from the need for life-long full-time care to independent living and professional success in adulthood. “That’s an enormous suite of possibilities to put into one bucket,” said Robinson.

There’s also heterogeneity within autism-associated genes. As sequencing data expands, said Robinson, “we’re starting to see a gradient emerging in the extent to which a gene can create risk for autism without commonly also causing global developmental delay or intellectual disability.”

One approach investigators take to studying the spectrum of outcomes looks at de novo variants—changes that occur in the sperm or egg and are therefore seen only in the child, not in the parents. Most of these variants are well-tolerated, but some are not. Through de novo variation studies, scientists have identified genes that are not tolerant to loss-of-function variation, in which one copy of the gene is disrupted.

“It’s estimated that about 10 percent of genes fall into this category,” said Robinson, “and 71 of them at this point have been associated with ASD at a genome-wide significant level.”

Of these 71 genes, 61 are also associated with intellectual disability. “In fact, most ASD-associated genes to this point have a stronger association with intellectual disability than they do with autism,” she said.

It’s been known for some time that strong-acting de novo variants that create risk for autism are more likely to be found in individuals with autism and intellectual disability and/or broader neurodevelopmental impairment.

More recently, investigators have learned that autism-associated genes related to intellectual disability and those associated with, say, schizophrenia are less overlapping than one would expect. “We’re beginning to be able to differentiate ASD-associated genes in terms of their phenotypic properties,” she said.

Another approach for studying ASD outcomes is looking at polygenic risk—the sum of many small effects from thousands of common variants across the genome. In people with ASD, higher polygenic risk score is associated with higher measured IQ, said Robinson.

“There’s been an enormous shift in [the severity] of ASD diagnosed over the last 30 years,” she said. The people who participated in ASD studies in the 1990s and 2000s generally had a very different behavioral and cognitive profile than people enrolled in current studies. “This shift is highly relevant to genetic studies, particularly [those] that are aggregating data over time.”

For example, the longitudinal SPARK study—funded by the Simons Foundation with 30,000 families enrolled—reveals substantially greater educational attainment, higher IQ and independent living in individuals diagnosed with ASD now compared with 30 years ago, said Robinson, when 70 to 80 percent of those diagnosed with autism met criteria for intellectual disability. In the United States and parts of western Europe, that rate has fallen below 30 percent in recent years.

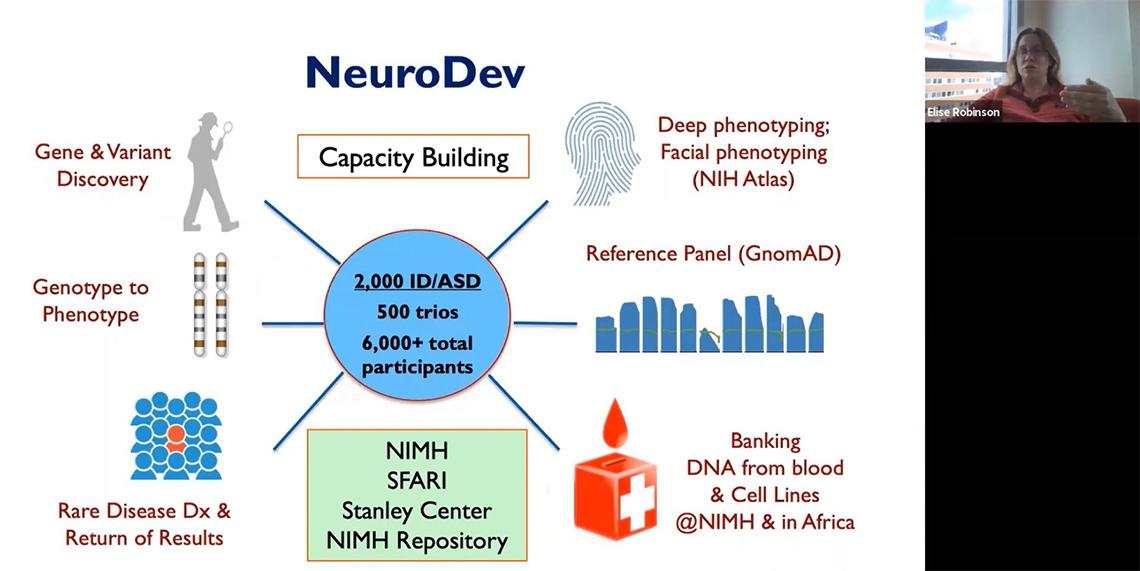

An ongoing data collection effort called NeuroDev has uncovered a different scenario in Africa.

“One of the unique things about NeuroDev [beyond] the genetic aspects,” said Robinson, is learning that “in different communities and different cultures…in this case in Kenya and South Africa, the type of autism that’s on average ascertained is much more similar to that which was ascertained in the U.S. about 30 years ago. On average, it’s much more severe.”

NeuroDev is collecting a range of cognitive, behavioral and medical data to study ASD and intellectual disability in Kenya and South Africa and will release the data publicly through NIMH at the study’s conclusion. With data from nearly 2,000 people, the project has already identified some novel candidate genes.

Another program, Matchmaker Exchange, may also help yield some clues about autism and potentially a range of other conditions. The program is collecting genetic data from clinical geneticists globally aiming to match deleterious variants, find overlapping phenotypes and ultimately identify causative genes for a range of syndromes and conditions.

Robinson’s lab so far has submitted 14 gene candidates to the exchange, variants they suspect may be causal for intellectual disability and/or autism. Through the exchange, she said, “We’ve already been matched with seven groups working on the description of novel genetic syndromes.”