‘Best Job in Biomedical Research’

Collins Reflects on 12+ Years as NIH Director

Photo: Bill Branson

A lot has changed at NIH and in the world since the mid-August day in 2009, when Dr. Francis Collins addressed a Natcher Bldg. audience on his first day as NIH director.

For the past nearly 2 years, of course, NIH and the rest of the globe have been thrust into a historic coronavirus pandemic that has taken the lives of more than 5.1 million people and dramatically shifted how humans interact with each other. The period has presented both enormous challenges and tremendous opportunities for the world’s largest funder of medical research, and for the organization’s leader.

Perhaps most surprising then is what has not changed since day one: Collins’s enthusiasm and energy for the job. On Dec. 19, he’ll step down after more than 12 years in the agency’s top seat, in part to make way for fresh leadership. Collins recently reflected on the mark his tenure leaves.

Master Communicator

Over his career, the longest serving presidentially appointed NIH director has gained a reputation as an accomplished science communicator. His ability to translate not only oftentimes gnarly concepts of medical research, but also the promise and hope of scientific enterprise in general, is tough to overstate. Collins attributed some of his ease with public speaking to his childhood.

“My father was a theatrical director and producer [and] my mother was a playwright, and I ended up onstage at an early age and loved that,” he recalled. He performed in a small 200-seat theater, which was beneficial because “you could see your audience and you knew if you were connecting or not.”

Photo: Ernie Branson

This experience first came in handy when he was a faculty member at the University of Michigan. “One of my big tasks was teaching medical students, and, if you want to be humbled by your own communication deficiencies, this is a great way to discover them,” he laughed. “They will turn you off really quickly if you’re not making sense on their level.”

In more public communication, Collins tries to consider the background of an audience and often formulates analogies based on that. “I always try to imagine…how [to] put forward what might be a complicated scientific concept in a way that would resonate,” he shared.

Flexibility is also important in communication, he added. Ask yourself, “Am I coming across here or do I need to modify the approach a little bit?”

He hearkened back to his theater audience-reading experience when speaking at in-person events, where he can gauge engagement and understanding in real time. It’s still possible in virtual settings, he added, though much harder to read body language through a screen.

The pandemic experience has reaffirmed the importance of science communication. While it’s a big part of his job as NIH director, communication is also “an important part of what all scientists are called upon to do,” Collins declared. “You need to be prepared at all times to describe your research in ways that anyone could understand, and you need to be aware whether the information you’re sharing is getting across.”

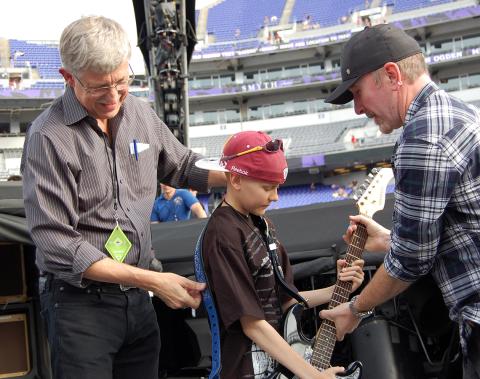

Rocking the House

Collins also frequently communicates through music, performing solo and with colleagues.

“For me, music lifts my spirits,” he said. “It’s good therapy and it’s an enjoyable way to share an experience with others.”

Photo: Ernie Branson

Collins spread the joy of music throughout the agency, playing piano for patients at the Clinical Center and rocking on guitar with his band, the Affordable Rock ‘n’ Roll Act (ARRA), at NIH events. Sometimes he’d write his own lyrics and serenade staff, students or conference attendees with such memorable originals as Amazing DNA to the tune of Runaway.

“When the band is really in the groove—with an audience who may be listening, or better yet dancing—and you’re up there on the stage with your scientific colleagues making a song just rock the house, that’s pretty special,” he said. “A lot of internal dopamine gets delivered at that moment.”

And speaking of how music affects the brain: “I do think there’s a lot we can learn about how music touches us in ways that can be uplifting and even healing,” said Collins, who, along with opera soprano Renée Fleming, has been a driving force behind NIH’s Sound Health initiative. Now in its fifth year, Sound Health unites neuroscientists with music therapists to study how music affects the brain and develop music-based therapies for neurological disorders.

“I think there’s a lot of promise there, and I love the idea of bridging what’s often seen as a gap between the humanities and the sciences,” he said. “Maybe as a guy who grew up in a theatrical family that also valued music a lot, this is for me an opportunity to bring together the various parts of who I am. And this clearly taps into similar hopes and dreams of a lot of other NIH scientists” who have enthusiastically joined the effort.

During the pandemic, Collins said he missed having live band gigs but made time to play and sing solo “just to try to change the dynamic a little bit of a very intense and busy day.”

Progress Report

The Collins era began with an outline of five priority areas he wanted to tackle: high-throughput technologies; translation of NIH science into practice; employing science to benefit health care reform; global health; and reinvigorating the biomedical research community through stable funding increases, high-quality training and diversity.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

“In each of those areas, some real progress got made,” he said. “Much of this progress has been greatly aided in the last 6 years by Congress coming around to an enthusiastic support of our need for sustainable, predictable increases in budgets, which has made it possible to start new projects.”

Collins pointed to advances in the technology arena—the BRAIN Initiative, stem cells and single-cell biology—and making sure developments in basic science successfully move into clinical benefits for patients.

“A big step was the creation of a new entity at NIH,” he said. “NCATS was a big push for me in the first couple of years as NIH director, to have a dedicated part of NIH that was focused on translational science. NCATS has been remarkably successful in that space.”

Collins wanted to make even further inroads in that area sooner.

Photo: Ernie Branson

“That’s one reason we’re now pushing forward this new concept of ARPA-H—a new division of NIH that could do even more about the gap between a scientific opportunity and it being turned into reality in a way that is going to benefit clinical practice,” he said.

In global health research, Collins talked about H3 Africa (human heredity and health in Africa), which “has supported dozens of institutions in 30 African countries, all working together in a network that has made it possible for a lot of cutting-edge science to emerge [across the continent]. There was a real risk of losing a lot of African talent because of the absence of opportunities.”

Another area where Collins had wanted to make much more headway is “diversity of our workforce, grantee community, and clinical trials participants...We recognized going back many years that we had work to do in this space. It’s been clear that the biomedical research community does not look, in terms of the diversity of the participants, like the country.”

NIH has made considerable strides intramurally through the Distinguished Scholars Program, Collins noted. Just beginning is the first extramural program also aiming to do cohort recruitment of tenure-track faculty with specific interests in diversity.

More comprehensively, NIH under Collins’s leadership has initiated a bold and unprecedented program through the UNITE initiative, aiming to address the long-standing problems of structural racism—both in terms of the workforce and how NIH’s health disparities research portfolio has been shaped.

Top Successes, Within and Outside

Photo: Ernie Branson

Asked what he sees as top accomplishments for NIH under his watch, Collins noted, for intramural research: clinical applications in cutting-edge genomic strategies for sickle cell disease “resulting in not just improvements in status, but what appears to be genuine cures; cancer immunotherapy efforts making it increasingly clear that activating the immune system can provide responses to cancer, even for people with stage 4 disease”; and securing funding from Congress after many years for the Clinical Center’s new surgery-radiology laboratory medicine wing.

But when history looks back at this era, he says, there will no doubt be much note taken of how the scientists in the NIH Vaccine Research Center were able to develop a Covid-19 vaccine in record time, and saved hundreds of thousands of lives.

Among extramural successes, Collins pointed to the BRAIN Initiative, “because this is a remarkable interdisciplinary effort to try to figure out how that really complicated structure called the human brain does what it does…In terms of basic science frontiers, it’s hard to go much deeper into the area of the unknown than the human brain. And we’re determined to sort that out.”

Collins also pointed to the “All of Us” program, which is recruiting a million Americans as NIH partners in a detailed study of factors that play out in health or illness.

“This is going to be a foundation for discoveries for decades to come,” he predicted. “This will be one of the things over the course of the next 20 years or so that people will look at and go, ‘Wow, that really made a difference.’”

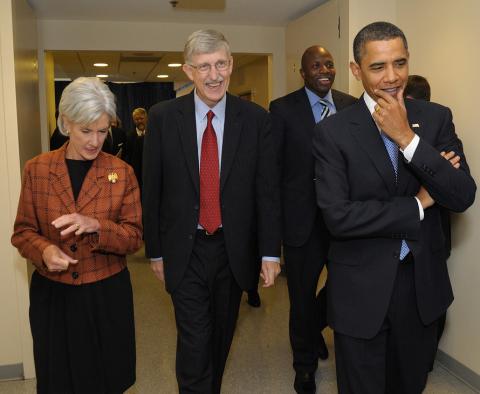

From One Director to the Next

After he was nominated as NIH director by President Obama, Collins spoke with Dr. Elias Zerhouni, who held the position previously. Zerhouni told Collins not to forget the “next generation of scientific talent.” Back then, budget cuts resulting from the country’s Great Recession were putting serious stress on higher education.

“[Zerhouni] was deeply worried we were in such a discouraging place for young investigators that we were going to lose a whole cohort of that group, never to return,” Collins said. “I heard that loud and clear.”

Collins launched the Next Generation Researchers Initiative, which supports early-stage investigators through specific funding and evaluation efforts. Before NextGen, the agency funded 600 grants from first-time applicants who were within 10 years of their highest degree. Over the past 3 years, NIH has funded more than 1,100 grants from the same applicant pool.

“Elias also talked about whether we were doing enough to build on the scientific capabilities that occur in the private sector,” Collins recounted. “That inspired me to think a bit more about what could be done.”

One result was the Accelerating Medicines Partnership, a public-private partnership that brings together top scientists from government, academia and industry to determine which research areas would benefit most from collaboration.

“AMP has emerged as a really powerful collaborative effort that just didn’t exist before,” Collins said.

Projects on Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease emerged. Recently, a new endeavor, the Bespoke Gene Therapy Consortium, was launched to speed development of gene therapies for the 30 million Americans who suffer from a rare disease.

Photo: Ernie Branson

If NIH’s next director asks him, Collins won’t hesitate to recommend another top priority: Build relationships with Capitol Hill lawmakers.

“Never turn down an invitation to meet with a member of Congress—even if you’re really busy,” he advised.

Despite Congress’s reputation for partisanship, he said, most members value biomedical research. In a dozen years, Collins estimated he’s had more than 1,000 one-on-one meetings with elected officials.

“These meetings almost always go well,” he explained. “Elected officials see what a remarkably important contribution NIH makes to finding answers to those health conditions that they’re worried about on behalf of themselves or their families or their constituents.”

Over the past 6 years, NIH’s budget has grown significantly. “That has a lot to do with the heroes in Congress,” he noted.

Peering into the Future

Research can take us in unexpected directions. Looking back, Collins never anticipated CRISPR gene editing would play such a dominant role during his tenure as director.

“Therapeutically, I’m really excited about where we’re going with gene therapy, that we might get to a point where those 7,000 genetic diseases where you know the DNA misspelling could actually be approached in a systematic way,” he said. “We’re starting to see some hope for that.”

Collins cited neuroscience as another field full of potential. “Along with that, I hope we’ll make major progress in dealing with the drug overdose crisis and the need to find better answers to chronic pain.

“And I’ve got to talk about vaccines,” said Collins, calling mRNA vaccines an amazing advance with potential beyond Covid-19. “mRNA opens up all these possibilities about how you might use these approaches [in other ways], like cancer. That’s going to be a big area we’ll want to invest in.”

Photo: Michael Spencer

Collins is also excited about the great strides in single-cell biology, “which has just transformed our ability to understand how life works and how disease happens.”

Anyone employing Collins’s practice of reading body language can see the obvious. Just thinking about the scientific potential ahead, the NIH director can hardly contain the infectious enthusiasm and energy that have become his signature. In a week or so, he moves away from the top post and returns full time to his firsthand research pursuits.

“I will tell you that [stepping down] was a tough decision,” Collins concluded. “I love the NIH. And this job is probably the best job in biomedical research, in terms of what one can do to shape research investments that are going to change people’s lives.

“Going through these 2 years with Covid, and seeing how the scientific community has risen to this challenge with things like the ACTIV partnership and the RADx initiative, as well as everything else that’s come out of NIH scientific commitments, has just been breathtaking. It’s also pretty exhausting, of course. The decision to step away was not an easy one. But 12 years is a long time to be in this position, longer than any previous presidentially appointed NIH director. And it’s a good thing for scientific organizations to have a turnover in leadership. After 12 years, it’s time for that.”