Let’s Talk About It

Texas Tech’s Hayhoe Kicks Off Sustainability Speaker Series

The first step in addressing any problem is talking about it. That’s especially true for climate change. And who better to start the conversation than Dr. Katharine Hayhoe?

An accomplished climate communicator who has made appearances everywhere from Jimmy Kimmel to the White House, Hayhoe is an atmospheric scientist and author. She is chief scientist for The Nature Conservancy and a Paul Whitfield Horn distinguished professor and the political science endowed chair in public policy and public law in the department of political science at Texas Tech University.

She spoke recently as part of a new series for federal employees hosted by the Office of the Federal Chief Sustainability Officer within the White House Council on Environmental Quality.

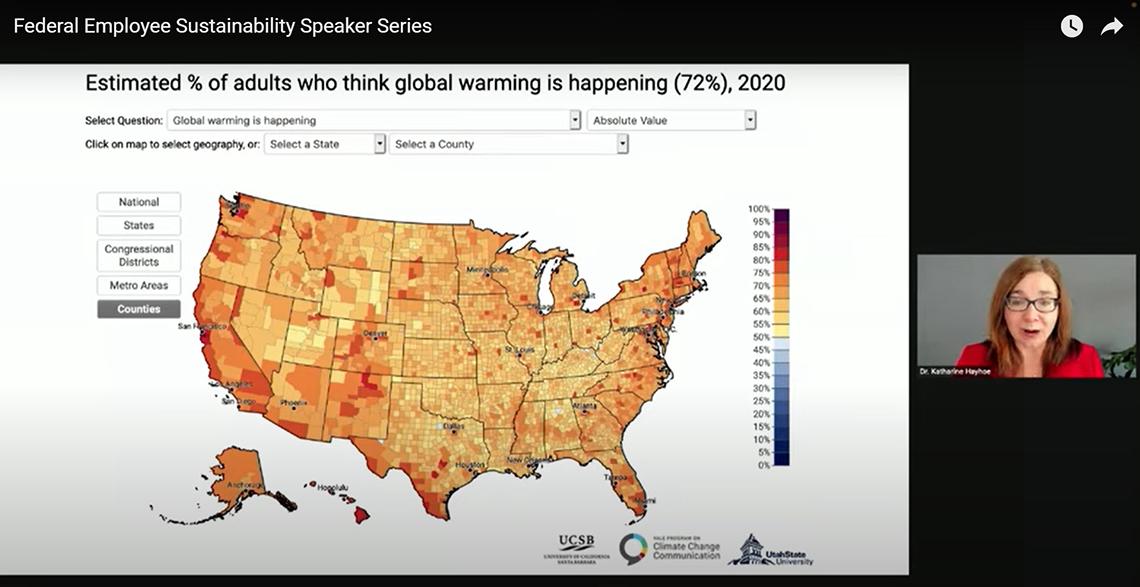

Seventy percent of Americans are concerned about climate change, according to a 2020 survey from Yale; and half of all Americans feel hopeless and don’t know where to start. Climate change “dismissives” are a shrinking minority—only about 8 percent of respondents in the Yale study. Hayhoe highlighted a different statistic: Only 33 percent of Americans discuss climate change regularly.

Talking about climate change is the first step in generating action, she said. “We talk about [it] because it affects every aspect of what humans need to survive and thrive on this planet.”

People have been studying the Earth’s climate for more than 200 years. French scientist Joseph Fourier discovered what we now know as the greenhouse effect (how the Earth’s atmosphere traps heat) in the 1820s and British engineer Guy Callendar was the first to prove that atmospheric carbon dioxide was warming the Earth back in 1938.

Over the course of human civilization, Hayhoe said, the Earth’s global temperature was as steady as the human body’s, fluctuating by no more than a few tenths of a degree over decades to centuries. Until the last 100 years, that is. Now, the increase in global temperature has reached the equivalent of a fever.

The power of fossil fuels has allowed for incredible advances in human society, but not without cost.

“As far back as we can go in the history of this planet, we have never seen this much carbon going into the atmosphere this quickly,” Hayhoe said. “We are truly conducting an unprecedented experiment with the only home that we have.”

The global temperature is currently 1 degree Celsius (almost 2 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than it would be without the impact of heat-trapping greenhouse gas emissions from human activities. That may not seem like a lot, but it is already wreaking havoc on weather patterns.

Some locations near Houston, for example, have had 3 “500-year flood events” in 3 years. The recent bushfires in Australia, flooding in Germany, last year’s heat wave in the Pacific Northwest—climate change made all of them more likely and more intense.

Burning fossil fuels produces air pollution as well as greenhouse gases; air pollution is responsible for at least 9 million deaths every year.

So, if we know climate change exists and the majority of Americans are concerned about it, why aren’t we acting at speed to fix it?

“It’s because we aren’t talking about it!” Hayhoe exclaimed. People experience a phenomenon called “psychological distance,” in which they acknowledge that a risk exists but don’t think it will happen to them.

In the 2020 Yale climate study, only 43 percent of those surveyed said that climate change will affect them personally. But it’s likely that climate change is already affecting us, wherever we are in the world.

Washington, D.C., for example, has seen an uptick in extreme heat over the past century. In the early 1900s it averaged 25 days of 90 degrees F or warmer. That number has almost doubled and is now 49 days as of 2020.

Hayhoe shared that she was recently in Iowa and was asked how to get people there to talk about things like polar bears and ice caps. “You don’t,” she responded. “You talk about corn.

“There’s no one you can’t connect climate change to, if you stop and take the time to figure out what they love, where they love and who they love,” she continued. You can make more of an impact if you talk about climate change on the local level such as unseasonable weather patterns, urban flooding, air pollution, etc.

Once you get people talking, the next step is to get them “activated,” Hayhoe said. Talk about what is already being done in their community and “[show] people how they can add their hand to that giant boulder and get it rolling down the hill even faster.”

Many people have probably heard the term “carbon footprint,” which are the carbon emissions that we are personally responsible for (such as driving a car). Hayhoe prefers the term “climate shadow,” which was coined by journalist Emma Pattee. A climate shadow describes how we influence others and model change.

One institution that has a large shadow, in terms of its influence, is the federal government. And the Federal Sustainability Plan has “one heck of a climate shadow,” according to Hayhoe.

The U.S. government has 300,000 buildings, 600,000 cars and trucks and annual purchasing power of $650 billion in goods and services. The new plan sets out five ambitious goals that will reduce emissions by federal operations, invest in clean energy and help communities become clean, resilient and healthy.

Federal Chief Sustainability Officer Andrew Mayock, who was also on the call, said that many federal agencies are ahead of these goals. NIH is proud to fall into that category, with 100 percent electric vehicle acquisitions for fiscal year 2022. The NIH Police Department also has 6 new electric motorcycles to offset emissions from the other vehicles in their fleet.

Working under previous presidential administrations focused on alternative fuel sources, NIH has already reduced its gas-powered vehicles to a mere 15 percent of its fleet. NIH currently has 9 electric vehicles and 2 charging stations on the Bethesda campus; 1 of the charging stations is offset by solar power. The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences in North Carolina will be receiving NIH’s first electric 24-ft. box truck.

NIH also provides incentives for employees to commute more sustainably, such as the Transhare Program for mass transit, free carpool and vanpool matching services, the NIH Bicycle Commuter Club, campus shuttles and the Electronic Vehicle Pilot Program.

We need systemic change to tackle climate change, Hayhoe said, but a system is also made of individuals. “We need to change the system so that the best choice is also the most affordable choice for everyone, [and we] need individuals because our voices are what change that system.”

Hayhoe admitted that a great deal of work lies ahead of us, but she remains optimistic. “We can’t go it alone, but together I really, truly believe we can do this.”

The next installment in the Sustainability Series will feature science educator Bill Nye. Visit https://www.sustainability.gov/index.html for more information and to view this archived lecture.

For more NIH commuter information, visit https://wellnessatnih.ors.od.nih.gov/worklife/Pages/NIH-Commuter-Information.aspx.