Urgent Response Required

Costs of Long Covid Becoming Clear

The toll of Covid-19 hospitalizations and deaths is just the tip of the iceberg, warned Dr. Ziyad Al-Aly during a Covid-19 scientific interest group lecture. The consequences of the infectious disease’s long-term effects lie just below the surface.

“We need to focus on the long haul and what’s beneath that tip,” said Al-Aly, chief of the VA St. Louis Health Care System’s Research and Development Service. Long Covid’s impact on disability and life expectancy rates and educational attainment in children “will have broad economic and social implications.”

“Long Covid” is an umbrella term for the lingering effects that result from a Covid-19 infection. It’s a multifaceted disease that can affect nearly every organ system, including the heart, brain and kidneys. Al-Aly estimates between 4 and 7 percent of patients who recover from the initial infection develop the condition. In total, there are about 30 clinical disorders that comprise long Covid. (NIH refers to the condition as Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection.).

Al-Aly first became aware of the existence of long-term complications of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, after reading a New York Times op-ed article by Fiona Lowenstein. She detailed her prolonged recovery from the virus in April 2020. Shortly after, Al-Aly saw self-reported surveys from patient-led groups suggesting that weakness, fatigue, brain fog and muscle pain were common.

“We asked the simple question, ‘What is long Covid?’” said Al-Aly. “We took a high-dimensional approach to leave no stone unturned and characterize the post-acute sequelae of Covid-19.”

Very early in the pandemic, he turned to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ electronic health care records—“an amazing and wonderful nationally integrated electronic health record system”—to shed light on the risks of long Covid. His team followed almost 74,000 veterans who had a Covid-19 infection for at least 6 months. He compared them with a group who did not have the virus.

His team found veterans who had Covid-19 were at increased risk for heart disease, diabetes, mental health conditions, kidney disease and nervous system disorders such as stroke, headaches and brain fog, and several other problems.

Even a year after publishing his initial results, Al-Aly said the “breadth of organ dysfunction” experienced by people with Covid-19 remains “really jarring.”

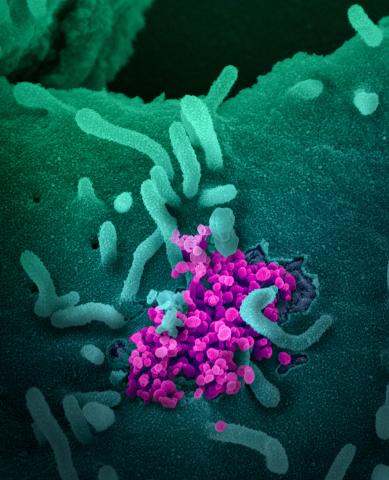

Photo: NIAID

The risk for developing conditions associated with long Covid was evident even in patients with asymptomatic or mild cases, he said. The risk was even higher in patients who were hospitalized and highest in patients admitted to intensive care.

The individual conditions that make up long Covid do not behave in the same way across age, race or baseline health status.

“Long Covid is not a monolithic entity. It does not all behave in the same way,” he noted. Some conditions, for example, occur more often in males and others occurred more often in females. However, the burden of risk was consistently higher in patients with severe Covid-19.

Al-Aly is most concerned about cardiovascular disorders, diabetes, kidney disease and neurologic and mental health disorders because these are chronic conditions that will last a lifetime and affect quality of life and life expectancy.

His team found that people with Covid-19 had an increased risk of several cardiovascular diseases, including cerebrovascular disorders, dysrhythmias, ischemic and non-ischemic heart disease, pericarditis, myocarditis, heart failure and thromboembolic disease. Patients with mild cases of Covid-19 had the lowest risk of developing one of these conditions.

The team also observed patients with the infection had an increased risk for diabetes within a year of being diagnosed with the virus.

“One to 2 percent who were exposed to SARS-CoV-2 might go on to develop diabetes,” Al-Aly said. “It’s easy for us to see it in a very large, big-data approach. But it’s much harder to see it in the clinics on the frontline.”

The pandemic has been a stressful and challenging time for many people. However, those who survived Covid-19 have a significantly higher chance of developing mental health problems—anxiety disorders, depression, substance use disorders and sleep disorders. In many cases, these patients were prescribed antidepressants, such as SSRIs and benzodiazepines.

Alarmingly, some patients with long Covid have returned to the clinic seeking pain relief. “We’ve seen early signals in our data—which I hope does not continue—of a resurgence of opioid use, specifically in people with SARS-CoV-2 infection,” Al-Aly warned. “That demands our attention to nip it in the bud.”

Vaccination against Covid-19 reduces the risk of long Covid, but not by much, he noted. People with breakthrough infections had 15 percent less risk of getting the condition. The risk reduction was most clear for blood clots and pulmonary sequelae.

“The best way to prevent long Covid is to prevent Covid in the first place,” he said. “If you haven’t encountered Covid yet, really, by all means, do your best to prevent yourself and your loved ones from having it.”

Long Covid is not rare, he said. Addressing the challenges posed by long Covid will require an urgent response from governments and health care systems. They must adapt quickly and establish post-Covid care strategies.

Al-Aly concluded by highlighting the role patients have played.

“My team would not be researching long Covid were it not for the wonderful patient advocacy groups who gave us strength and warmth in our hearts to pursue this,” he said. “This has been a challenging journey. Had it not been for them we would not be here.”