Skin Protection

NIAID Fellow Uncovers the Skin’s Natural Immunity

Everyone’s skin may be tougher than they realize. Research led by Dr. Inta Gribonika, a postdoctoral NIH fellow, demonstrates that skin is more than simply a cover from the outside world; it can offer a first line of defense against infection, paving the way for new kinds of therapies.

Gribonika recently completed a four-year stint as a visiting fellow in the Laboratory of Host Immunity and Microbiome at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). During her time at NIH, she contributed new knowledge about the skin’s role in immune response, research that recently was published in Nature.

Her findings show that the skin can act as a lymphoid organ. In other words, a specific immune response can actually be primed in the skin.

Gribonika is a mucosal immunologist. Her doctoral research had focused on how an immune response could be induced in the gastrointestinal tract after vaccination. After reading that the bacteria living naturally on skin is coated in antibodies, she began to wonder how the body could generate antibodies—which it normally would do against an infection—around something that’s generally harmless.

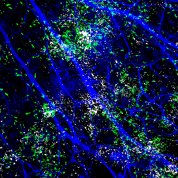

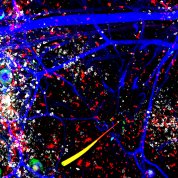

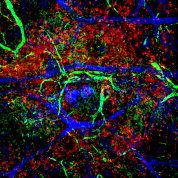

“Up until now, we were thinking that B cells—the lymphocytes that produce antibodies—were not living in the skin or coming toward the skin tissue at homeostasis,” she said. Her experiments show that B cells do exist in healthy skin.

In the lab, Gribonika painted a beneficial bacterium, S.epidermidis, onto the skin of mice. This bacterium is commonly found on human skin, but not on mice.

“I showed that, indeed, skin can recognize this new harmless member of microbiota and generate specific humoral immunity against it,” she said. “This can happen without any help from professional immune organs, such as the spleen or lymph nodes.”

The antibody works as a barrier protection, Gribonika said. “It works as a health insurance in case this one new member of commensal microbiota that we now acquired decides at some point in the future to become nasty and infect us.”

The ability of harmless bacteria on the skin to stimulate an immune response without inflammation opens a world of possibility for topical medications and vaccines. They could be formulated in a cream that anyone could apply to the skin.

“This route is so interesting because it’s noninvasive and you wouldn’t need a clinical practitioner to help you apply the medicine,” Gribonika said.

In reflecting on her time at NIH, Gribonika emphasized how much she enjoyed getting to know the people in the lab. Each investigator had his or her own project, but they all supported each other. And they came from all over the world, bringing their different cultures and perspectives, which she found especially enriching.

“NIH is probably the best place on Earth to do research,” she said. “There are so many resources, and the community is so welcoming and willing to share.”

When she arrived at NIH, Dr. Yasmine Belkaid was her lab chief. She described Belkaid as a visionary who encouraged her trainees to think big. “She gave me the space and freedom to ask the questions I wanted to pursue,” Gribonika said.

Photo: Sergei25/Shutterstock

Gribonika first became interested in science at a young age. “My mom and dad would always read to me about great discoveries and about the people who made them,” she recounted. These stories sparked her imagination and got her thinking about nature and the world from different perspectives.

“I got interested in science to question what’s there—what we can see and what we can’t see,” Gribonika said. “Immunology is heavily focused on microscopy, on the things we don’t see just by looking at our skin. But if you ask the right questions and use the right antibody to target the right thing, all of a sudden you see all these interesting things happening in and on the skin.”

Gribonika is a native of Latvia, a small northern European country with less than two million people. As her friend Daina Bolsteins, an administrative assistant at NIAID who is also of Latvian descent, noted, “Latvia is better known for producing basketball and hockey players, opera singers and symphony conductors than for producing scientists.” Gribonika said she hopes her story will inspire other aspiring scientists from her country.

In March, Gribonika headed to Sweden to begin a new chapter as a tenure-track investigator at Lund University.

Her advice to young investigators? Never give up. Remember why you chose this path in the first place, she said.

“If the data disproves your hypothesis, follow the data. If the data conflicts, repeat with other methods and protocols. Be cautious. Verify.”

Such rigor in research, she said, opens the door to learning new concepts about the human immune system and overall health.

“Results will take you to places you never thought of,” she said. “There’s a lot of novelty out there.”