‘Sacred Mission’

Former NIH Director Describes Experiences That Shaped His Journey

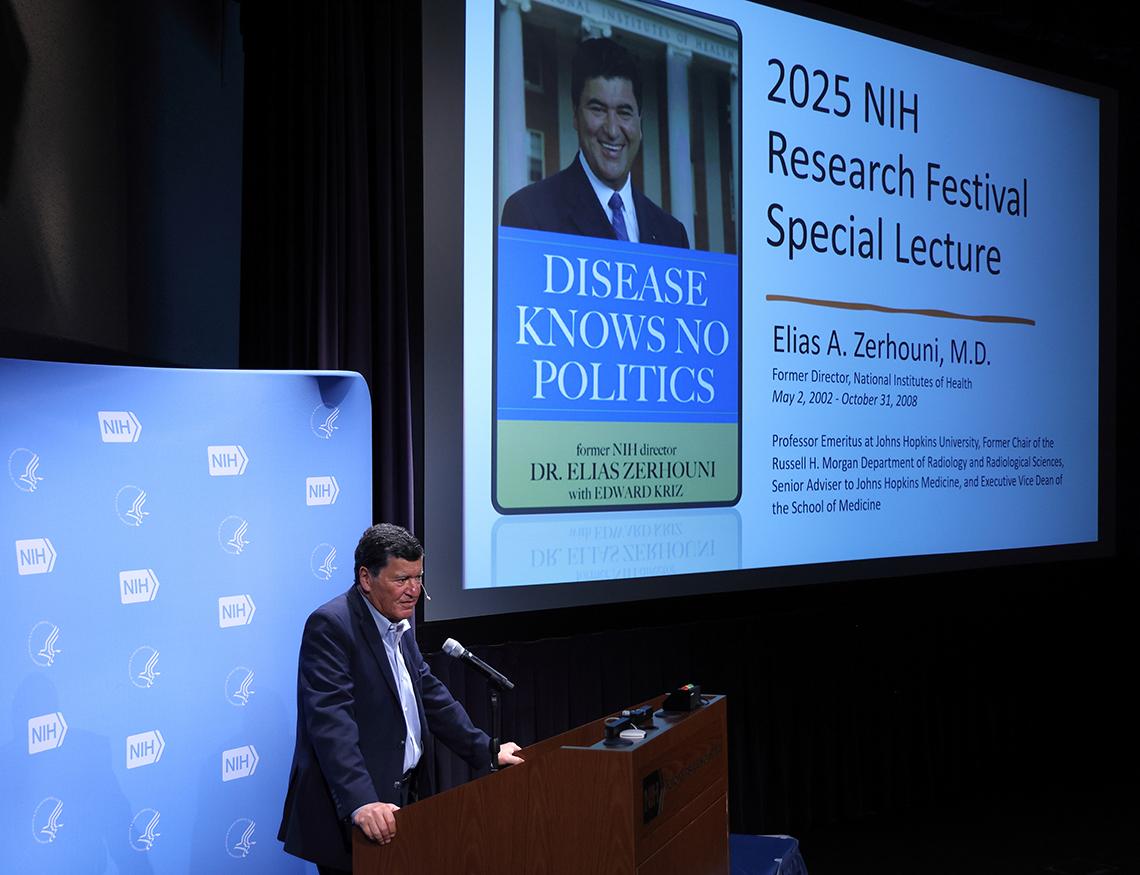

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

Dr. Elias Zerhouni first publicly uttered the phrase “disease knows no politics” during his first congressional hearing 23 years ago. Soon after, in May 2002, Zerhouni was sworn in as NIH’s 15th director. Now, that phrase serves as the title of his newly published memoir, which he discussed at a keynote lecture at the NIH Research Festival.

At that confirmation hearing, Zerhouni had touched on themes that became a hallmark of his career—multidisciplinary research, training and retaining the best scientists—while treading carefully when discussing his position on a particularly polarizing issue at that time: human embryonic stem cell research.

“It was quite a hot political potato at the time I was appointed [NIH director],” Zerhouni recounted. “How I would handle that was critical to both the credibility of NIH and the credibility of science.”

At that hearing, he reiterated his conviction about the NIH director’s role. “The NIH director should be impartial and nonpartisan,” he said. “We represent something much bigger than us.”

The American Dream

“I’m an immigrant,” Zerhouni declares proudly, in awe of having had the opportunity to rise to such prominence in the U.S.

Born in Algeria, he spent his formative years in the war-torn country, which had a profound effect on him. “Oppression is an experience you never forget,” he said.

During the Algerian War, schools were closed for long stretches, impelling young Zerhouni to find new ways to learn. His father was a teacher but had to split his time among their large family.

“So I learned to learn by myself,” Zerhouni said. “I developed a mindset about learning and that stayed with me.”

Zerhouni is the fifth child of seven boys. He had a sister, Chahida, who died when she was 18-months old of measles, a disease that would later be preventable by vaccination.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

Zerhouni grew up loving science and exploring new ideas. But his bad handwriting led him to stop taking notes. He vowed, “I’m going to listen more carefully to what people say but also synthesize it and crystallize it—because you can’t remember every word—at the same time.” This skill, he noted, would help during future Senate hearings and in compiling the hundreds of ideas collected toward creating NIH’s Roadmap.

After graduating from medical school at the University of Algiers and marrying Nadia, his childhood sweetheart, Zerhouni and his wife headed to the U.S. He entered the radiology residency program at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore.

“My intention was not to immigrate to the U.S.,” Zerhouni recalled. “I wanted to learn bioengineering and imaging and return to [Algeria].” He’d planned to work at the new hospital when it was built. But instead of a public hospital, the Algerian regime built a military one, which Zerhouni didn’t want to join.

“Life is not a golden plan,” he said. “There will be surprises and opportunities, so go with it. But there are principles and values that you cannot ignore.”

Second Home

Zerhouni would come to consider Hopkins his home away from home. He ultimately would spend 20 years there pioneering imaging research, chairing radiological sciences, teaching.

“Many people don’t appreciate how important research universities are,” said Zerhouni. “When I came there, I was immediately embraced as someone who had ideas and quickly learned the value of a research university as the place where you train, where you create intellectual talent, and you’re mentoring the next generation of scientists and doctors.”

Zerhouni was never afraid of trying something new, and he dove in eagerly across the fields of imaging: CT scans, MRI, ultrasound. Then he hit a wall.

“There was something in science standing in [our way]—the siloed nature of disciplines, departments and institutes.”

He was growing frustrated. “I wanted to do research that required me to have a physicist on my team, a radiology engineer, a computational scientist, a biologist,” he said, but he couldn’t form that team in the existing system. Zerhouni brought the discussion to the top at Hopkins and, ultimately, through permissions among departments and dual appointments, he recruited and formed his multidisciplinary team.

“We were going to be stymied,” he said, “if we didn’t understand how to organize scientific teams differently for the complexity of the issues we were dealing with.”

NIH Rocks

Once confirmed as NIH director in 2002, Zerhouni arrived to find a similar hindrance. Institutes and centers were siloed. Zerhouni quickly set out to foster more cross-collaboration. He invited hundreds of scientists to share ideas and concerns and help define new goals toward a new strategic plan.

“Science may have moved from the structure of NIH,” Zerhouni had acknowledged. “Are we missing fields of science that because of our structures, we cannot fund them, we cannot advance them?”

NIH collected nearly 1,000 responses. Sifting through them led to Zerhouni’s “rock, pebble, sand” strategy. Most ideas are pebbles and sand. He said we need to find the rocks, the ideas that could lead to high-impact changes. From this process, multiple themes emerged. The rocks included training the next generation of scientists, addressing the complexity of biological systems and re-engineering the clinical research enterprise.

The ideas crystallized into the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Within the Roadmap, the Common Fund was created and ultimately signed into law within the NIH Reform Act of 2006. This appropriation would fund high-priority projects that cut across multiple disciplines and institutes.

Zerhouni’s memoir, he said, recounts “a complex journey that represents and reflects fundamental values of our country, of our scientific enterprise, of NIH at the core of it.”

The book is filled with lessons learned throughout his life and career. Don’t limit yourself; consider different perspectives and approaches. “If we stifle uniqueness, we bury genius,” he wrote in his memoir.

On life’s journey, take calculated risks. Be curious, humble and compassionate. Be good stewards of our intellectual capital, he said. “Science is an investment in the future.”