Mucins and Mentoring

Ten Hagen Inspires at Research Fest

“Life will take you in many different directions, so enjoy the ride.”

Dr. Kelly Ten Hagen of NIH’s National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) delivered this advice as the 2025 honoree for the yearly Anita B. Roberts lecture series. This lecture highlights the research achievements of women scientists at NIH. Its namesake was an exceptional mentor and scientist who served as a lab chief at NIH’s National Cancer Institute (NCI).

At the NIH Research Festival, Ten Hagen shared her research and recounted her career journey. Ten Hagen, a senior investigator and chief of NIDCR’s Developmental Glycobiology Section, was born and raised in western New York. She initially wanted to be a veterinarian when she entered Cornell University as an undergraduate.

As her interests evolved, she changed to a pre-med track before taking a research position in a Drosophila (fruit fly) laboratory that led her to pursue a Ph.D. She earned her doctorate in genetics at Stanford University and later returned to New York, where she became a research assistant professor in the lab of her future NIH colleague, Dr. Lawrence (Larry) Tabak at the University of Rochester. Her research in her own NIH lab studying mucin-type O-glycosylation stems from her work with Tabak.

Mucins and O-glycosylation, much like life, can take a researcher in many different directions. O-glycosylation describes a process in which a sugar molecule is attached to the oxygen atom in the hydroxyl (OH) group in a process called glycosylation. In mucin-type O-glycosylation, the sugar is attached to the hydroxyl group of a serine or threonine amino acid residue within the mucin protein. This process happens to all known mucins, which are the main component of mucus.

Mucus is “the first line of defense between your environment and your epithelial cells,” Ten Hagen explained. “Diseases where mucins aren’t made or are made improperly can have very severe consequences.”

Her lab studies how mucins are synthesized, what glycosylates them and how the proteins’ unique properties are conferred.

A family of enzymes called GalNAc transferases are responsible for transferring the sugar (GalNAc) from its donor molecule to a serine or threonine on a protein. Humans have 20 different GalNAc transferases. Ten Hagen’s lab is studying how dysregulation of some of these enzymes can cause disease.

In one example, a GalNAc transferase abbreviated as GALNT11 was associated with kidney function decline in a GWAS [genome-wide association study] of people of European descent. As Ten Hagen dug deeper, she learned that GALNT11-deficient animals display a condition called proteinuria, in which proteins are lost into the urine because the animal can’t properly reabsorb them. Interestingly, in a portion of the kidney dedicated to reabsorbing proteins, the main endocytic receptor responsible for nutrient reuptake (megalin) is normally glycosylated by GALNT11, allowing it to function properly.

Additionally, missing or mutated GALNT11 has downstream effects on mineral homeostasis and bone composition.

Another condition, hyperphosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis (HFTC), is associated with mutations in the GALNT3 transferase. Patients experience dysregulation of blood phosphate levels, leading to painful calcified masses in their soft tissues and vasculature. There are no effective treatments. Ten Hagen collaborates with Drs. Michael Collins and Kelly Roszko at the NIH Clinical Center to treat these patients and understand the basis of disease.

Dr. Liping Zhang, a staff scientist in Ten Hagen’s lab, designed a cell culture system to study patients’ individual mutations and develop targeted therapeutics.

With this cell culture system, Ten Hagen said, “We can design strategies to increase the activity of GALNT3 in situations where a mutation causes low levels of activity, or increase the stability of those that appear to be misfolded.”

Mucin secretion is often disrupted in diseases of the oral cavity and digestive system. If Ten Hagen could image the mucin biosynthesis and secretion process in real time, then she could determine a healthy baseline to compare to the diseased state.

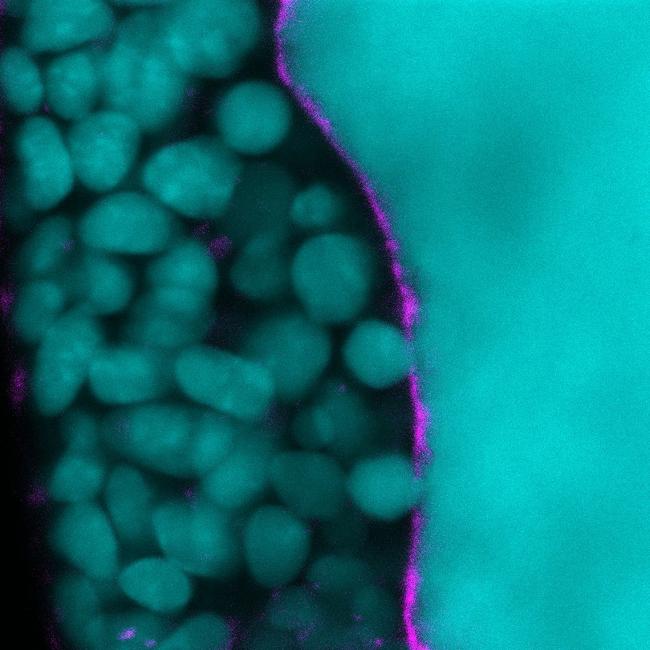

She conducted the imaging in an unlikely subject: Drosophila salivary glands, whose secretory granules (the “packaging” that holds the mucins) are 10 to 100 times larger than in mammals. The process of packaging the mucins is “one of the longstanding questions in this field,” Ten Hagen said.

Photo: Duy Tran/NICDR

Her former postdoc Dr. Duy Tran set up this system to image mucin production, packaging and secretion in real time in a living organ. Another former postdoc, Dr. Zulfeqhar Syed, conducted imaging to show how mucins are restructured and compacted within secretory granules.

“A mature granule contains multiple distinct mucins that are restructured in a way to have intragranular segregation of the mucins, which may be a precaution, so the mucins don’t ‘gum up the works’ when they are secreted,” explained Ten Hagen.

But what about when the mucins are malformed? They cannot compact properly within the secretory granules, eventually causing them to rupture.

“We believe mucin compaction is important in terms of the stability of the granules and secretory cells,” she said. Understanding how different mucins are packaged into and secreted from secretory granules may help researchers better understand diseases resulting from defects in mucin secretion.

Ultimately, Ten Hagen’s lab seeks a mechanistic understanding of how aberrant O-glycosylation contributes to disease, in order to design novel therapeutic strategies.

In addition to recognizing her scientific accomplishments, the lecture also honored her contributions as a mentor.

“I feel incredibly fortunate to have been mentored by someone who exemplifies integrity, generosity and intellectual curiosity,” said Dr. Alyssa Lee.

Dr. Carolyn May found a staunch advocate in Ten Hagen: “I was told to tone down my feminine voice during my process of applying to medical school, but Dr. Ten Hagen stood firmly by my side. Her unwavering support reaffirmed that my voice belonged in medicine, and Dr. Ten Hagen embodies the kind of mentor who not only trains scientists but shapes future leaders.”

A recording of the lecture is available at https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=56707.