Progress Report

Vallabh Prepares for First Clinical Trials for Prion Disease Therapeutic

When Dr. Sonia Vallabh visited NIH five years ago, she was on the hunt to find a treatment for a rare disease encoded in her own genes. The patient-turned-researcher carries the gene for an inherited prion disease called fatal familial insomnia. She and her husband Dr. Eric Minikel have devoted their lives to finding a cure and now they’re closer than they’ve ever been.

Vallabh returned to NIH in December to deliver the Wednesday Afternoon Lecture: “A Patient-Scientist Lens on How and Why to Move Faster to First in Human.”

Prion protein, in its native form, is a protein that exist normally in mammalian brains. In rare cases, it can spontaneously misfold into a “prion” and spread throughout the brain, forming clumps that damage or destroy neurons and cause neurological symptoms. Prion protein, abbreviated PrP, is encoded by the PRNP gene.

All prion diseases can be divided into three subtypes: familial, sporadic or acquired. Patients with the familial form—like Vallabh—can be identified while still healthy, and she thinks that lowering levels of PrP should benefit both pre-symptomatic and symptomatic individuals.

“PRNP loss of function alleles occur in the population at a rate of 50 per million—exactly what would be expected if natural selection didn’t mind it,” explained Vallabh. While researchers are still trying to elucidate the exact functions of PRNP, it seems that losing the gene isn’t detrimental enough for nature to safeguard against it.

“There’s still a lot we don’t know about prions,” she added. “But I think we know enough to develop meaningful therapies.”

Her lab is doing just that. They currently have two prion-lowering modalities that they are working to develop in-house: an oligonucleotide and a gene editing tool.

Oligonucleotides are short sequences of chemically modified nucleotides (the building blocks of DNA). They can be built to target specific stretches of RNA to turn genes on or off, blocking the expression of harmful proteins and more.

The oligonucleotide Vallabh is developing is a divalent, small-interfering RNA oligonucleotide (di-siRNA). siRNA triggers the RNA interference process to target and destroy the messenger RNA of a target gene. The divalent format of this technology was developed by Dr. Anastasia Khvorova at the UMass RNA Therapeutics Institute, with whom Vallabh’s lab is collaborating. By linking two siRNAs together, Khvorova and her team created a structure that appears to be active for up to six months post-dose and distributes widely across the brain.

The oligonucleotide is delivered through the cerebrospinal fluid and must be dosed periodically as the drug is metabolized.

The research that Vallabh and her team have conducted in animal models has led her to believe the therapy “absolutely seems worth advancing.”

Vallabh and her husband received an investigational new drug (IND) clearance from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in March 2025 to test the di-siRNA therapy in humans. Clinical trial preparations are now underway at five locations in the U.S., and Vallabh is hopeful they could dose their first patient in early 2026.

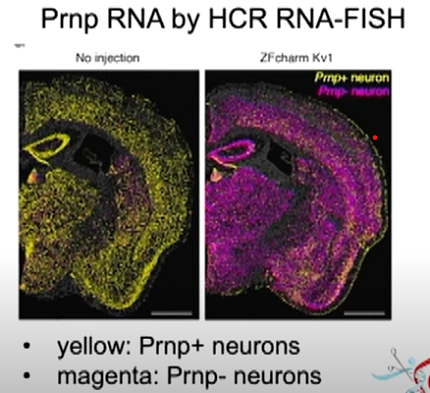

The other therapy she discussed was the epigenetic editor CHARM, which stands for Coupled Histone tail for Autoinhibition Release of Methyltransferase. This tool, developed by Dr. Jonathan Weissman’s lab at the Whitehead Institute, works by adding methyl groups to the promoter section of the PRNP gene, silencing it. CHARM may be less risky than a gene editor because it modifies how the prion gene is read rather than making edits to the actual genetic code.

“Three years ago, I wouldn’t have bet on gene therapy for our disease,” Vallabh said. This was because of the difficulty of delivering gene therapies across the entire human brain, which will be essential to make a difference in prion disease. However, recent advances in delivery methods have made her more optimistic that this approach is worth trying. Her lab is working with Dr. Ben Deverman, a fellow Broad investigator, and his team, which recently developed a viral vector that binds the human transferrin receptor in order to cross the blood-brain barrier. Vallabh is hopeful together, they will file an IND in 2027.

As a patient-scientist, Vallabh is sensitive to the needs of her potential patients. “What are we asking of people who go on this therapy?” What will their futures look like, if they receive a “one-and-done,” irreversible therapy like CHARM versus a therapeutic like the di-siRNA oligonucleotide that can be halted if needed, but will require repeated doses if helpful? Companies that manufacture rare disease drugs cannot always afford to continue making them. What happens to the patients who depend on those drugs if they lose access?

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

Vallabh’s unique patient-scientist perspective also begets a unique drug development process. Her lab publicly shares as much information as possible, displaying everything from their data and results to their regulatory submissions and related feedback from the FDA. If the new treatment modalities her lab is testing prove helpful against prion disease, she is hopeful that they may also prove useful against other diseases of the central nervous system.

As she phrased it, “Fast human learning helps all boats rise.”

Even with all the progress her lab has made, the amount of work ahead of Vallabh is immense.

“We have so much now that I could not have even imagined when we first started down this road,” she said. But still, “when a patient reaches out to me, which happens basically every day, what I have to say to them is ‘right now, there’s nothing.’”

About 600 people die of prion disease in the U.S. each year; even once the upcoming di-siRNA clinical trial launches, this small first-in-human study will not be able to enroll the majority of patients who reach out.

“I can tell you at any given time who in my community is actively dying of prion disease today because we didn’t get there fast enough for them,” she said. “To have come so far and still have so far to go…I wouldn’t have imagined it this way.”

Vallabh said one bright spot is her children. They were conceived via in-vitro fertilization (IVF) pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) and were tested as embryos for her PRNP mutation, for which they are negative. For now, she speculates, maybe this is the ultimate form of prevention.

“I’m going to fight for prevention for the people who are living and at-risk today,” she said.

“And, however it goes, I want [my kids] to know that I fought for this.”

A recording of the lecture is available at https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=57108.