NIAMS Jumpstarts Volunteer Response to Coronavirus

Photo: Keith Sikora

When an NIAMS intramural researcher became the first NIH employee to test positive for the novel coronavirus on Sunday, Mar. 15, NIAMS mobilized. By the next morning, the institute had sent out an email to its clinically trained staff and had recruited five volunteers to help mitigate the spread of the virus on campus.

“The speed of the response was quite striking to me—not surprising, but striking,” said Dr. Robert Colbert, director of the NIAMS clinical research program. “Because we had the index case, we got involved very quickly in the process of working with OMS [Occupational Medical Service], which was already being overwhelmed with calls from NIH staff about symptoms.”

Volunteers from across NIH joined the early NIAMS staffers to create a robust system for screening, testing (“swabbing”) and monitoring members of its workforce who show symptoms of the COVID-19 virus.

The screening process continues to change in response to the rapidly evolving situation. At the time of this writing, here’s how it works.

Rigorous screening for NIH staff

If NIH’ers are concerned they are infected with the virus, the first step is to contact their health care provider. Next, they should complete the OMS online questionnaire. This screening tool is available to the entire NIH workforce, including federal employees, contractors and trainees. It is designed for those who have symptoms of COVID-19 (the disease caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2) and believe they were exposed to the virus in the previous 14 days.

Every NIH’er who completes the questionnaire will receive a call from an OMS staff member or volunteer who will help determine the next steps for each person. Ly-Lan Bergeron, a physician assistant at NIAMS, is one of these volunteers.

“You have to go through multiple questions with each employee, trying to figure out if they qualify for swabbing or not, whether they should be monitored…whether they can go back to work or not,” Bergeron explains. “It’s definitely interesting.”

When the screening began in mid-March, OMS was inundated with calls. Many NIH travelers returning from overseas feared they had been exposed to the virus.

“Initially, there were so many calls,” Bergeron says. At the time, she was making up to 10 calls a day. “Now things have toned down,” at least partly, she says, because travel (and its risk of exposure) has been curtailed.

In addition, the screening process has been improved and streamlined. For example, in the early days of the response, before the online questionnaire had been developed, telephone screening was done in hard copy (on paper) by volunteers sitting in FAES classrooms in the Clinical Center.

“They spaced out the workstations at least 6 to 10 feet apart, and each station was numbered,” Bergeron recalls. “We noted the number of our seat and had to wipe down the station with sterile wipes before we used it. Eventually we were required to wear masks in the room.”

Now, volunteers can make the calls from home and log responses electronically.

Clinical Center screening

The Clinical Center initially limited the number of patients admitted to the hospital, canceled or postponed outpatient procedures and restricted visits from family and friends. But this policy was due to be loosened toward the end of May.

The main cafeteria is closed, as is the gift shop, hair salon and credit union. Still, hundreds of people enter the building every day—doctors, nurses, patients, housekeeping staff, those who bring in food, deliver packages or care for research animals. Every one must undergo in-person screening and evaluation.

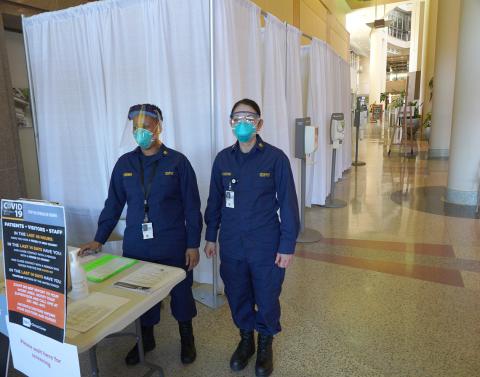

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

When people enter the Clinical Center, they are directed to one of the privacy booths erected in the north lobby. There, they are greeted by an NIH clinician or Public Health Service officer dressed in personal protective equipment. The clinician gives the person a surgical mask and a squirt of hand sanitizer, then asks a series of questions: Why do you need to enter the hospital? Do you have any of the following symptoms? Recent travel? Known exposure to the virus?

Depending on the answers, the person is asked to leave the hospital (if the visit is for non-essential business), allowed to enter (and required to wear the mask while inside) or asked to self-isolate and call OMS. When leaving the booth, the person’s hands are treated again with sanitizer.

People who have clear symptoms of coronavirus are escorted to a special COVID-19 testing area within the hospital.

NIAMS nurse practitioner Alice Fike is one of those who screens people coming in the hospital’s entrance. She is also a commander in the Commissioned Corps. After several weeks of volunteering, she was officially deployed to help with the Clinical Center’s coronavirus response.

“We’re trying to keep any virus out of Bldg. 10, which now contains only the sickest, most vulnerable patients,” she says.

Testing for the virus

Only a portion of NIH’ers screened for the virus will need to be swabbed for it. Still, it’s a big job.

To test workers who have symptoms of COVID-19, NIH assembled its volunteers into teams. Each team includes a greeter, two swabbers (who use a long sterile swab to take tissue samples from deep within the nasal cavity), two swab assistants (who package the samples) and a labeler. A safety officer monitors the operation for unsafe situations and to develop measures for assuring personnel safety.

April Brundidge, a research nurse with NIAMS, has rotated among all the roles. Her many previous volunteer experiences include helping at homeless shelters in Florida and Virginia, administering vaccines to children in Hawaii and teaching workers in Liberia how to conduct a vaccine trial during the Ebola crisis.

“This volunteering experience feels different,” she says. “I know I’m here to help, but it’s very eerie driving onto an empty, quiet campus. It feels like I’m a character in a sci-fi movie.”

Like Brundidge, nurse practitioner Carol Lake has extensive volunteer experience. She came to NIH less than 6 months ago and works for both NIAMS and NHGRI. She was credentialed as a specialist in rheumatology in February—just 3 weeks before non-essential employees were asked to work remotely. For years prior to that, she provided primary care and infectious disease control in an outpatient community clinic. In a way, this new volunteering experience is a return to her roots as a generalist.

“Honestly,” she says, “I feel more comfortable [helping with the COVID-19 response] than seeing patients for rheumatology.”

NIAMS intramural researcher Dr. Keith Sikora works as a swabber. “I volunteered because I’m a physician first,” he says. “I became a doctor to help people.”

Sikora describes the swabbing process as “very methodical. We follow very special steps to clean ourselves between each patient…I’ve been very satisfied with how we were trained to prevent transmission to the volunteers.”

Nonetheless, he says, “I think we all just want everything to get back to normal.”