Early Alternative Medicine?

Historian Looks at Hypnosis, Hype and Health

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

Entranced girl. Caged lion. Fascinated audience. Clever carny. Reads like all the ingredients for a reality TV segment, but this particular recipe was ripped from 19th century French headlines. What’s more, the sensational mauling death that resulted from the incident in Beziers, France, wasn’t even a unique occurrence.

Mind control, whether it was possible and who should be allowed to practice it were all fodder for a recent NLM History of Medicine lecture, “Girl in the Lion Cage: Regulating Hypnotism in 19th Century France,” by Dr. Katrin Schultheiss, associate professor and chair in the department of history at George Washington University.

“The phenomenon of hypnosis was of immense interest to doctors and researchers as well as the general public in the 19th century,” she said. “While the scientific community debated—heatedly at times—whether susceptibility to hypnotic suggestion was a sign of nervous pathology or a normal feature of the human mind, the general public marveled at the seemingly limitless and potentially dangerous ability of one mind to control another.”

In the event described above, Schultheiss said, “the hypnotist’s goal was to demonstrate to the gathered crowd how profound and authentic [the girl’s] hypnotic trance was—so profound that she would neither protest nor show fear when introduced into the cage, so profound that the lion would presumably show no interest in her.” Which, of course, is not how things turned out.

But to some in the medical community—especially the esteemed Dr. Jean-Martin Charcot, widely regarded as the father of modern neurology and a recognized expert on hypnotism—such staged theatrics represented much more than tragic circus: It amounted to practicing medicine without a license, or even proper training.

A similar mauling had already occurred in another part of France weeks earlier. That victim, also a young female, survived the lion attack. Still, the dangers of just anyone using hypnosis seemed clear to Charcot.

He and others believed “susceptibility to hypnotism and hypnotic suggestion was a sign of underlying hysteria, a sign of neurotic pathology,” reported Schultheiss. And since the subjects were ill, any attempts to delve into their minds ought to be governed by professional codes and standards.

“The need to regulate hypnotism stemmed from a belief that there were people with latent hysteria whose pathology could be triggered by exposure to hypnotism outside of a medical setting,” Schultheiss said.

Then and now, Charcot’s voice carried a lot of weight in scientific and medical communities. He was the first to describe multiple sclerosis. His work laid the foundation for our early understanding of Parkinson’s disease. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, was first known as ”Charcot’s disease,” owing to his observations of the disorder. He taught renowned Austrian founder of psychoanalysis Dr. Sigmund Freud.

Using medical illustrations, scientific journals and Charcot articles and correspondence found in NLM’s History of Medicine collections, Schultheiss is putting the finishing touches on a book about the pioneering neurologist’s other work, however—his somewhat sketchy theories about hysteria and his use of hypnosis as an entryway into the recesses of the mind.

During the 1880s to 1890s, Schultheiss said, hypnotism was having something of a heyday as “public, legal and medical interest skyrocketed across Europe…No one bore more responsibility for introducing the public to the practice of scientific hypnotism than Charcot.”

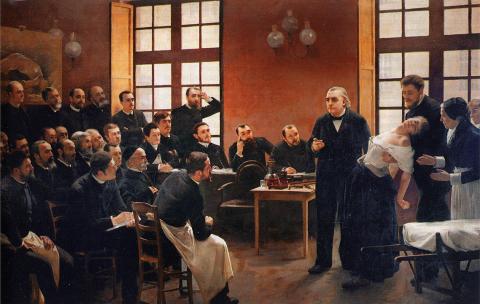

In 1882, at the prestigious Academy of Sciences, Charcot argued for hypnotism’s legitimacy with a paper describing three phases of the practice. At Salpêtrière Hospital, which had become a famous neuropsychiatric teaching center, he routinely conducted his own demonstrations, always employing female subjects. The hip crowd attended these exhibitions, too. Audiences often included politicians, artists and authors as well as neurologists, ophthalmologists and psychologists.

Multiple factors occurring at the same time helped set the scene, Schultheiss recounted. In mid- to late-19th century Europe, there were, for instance, “overall efforts to regulate medical practice, trepidation about the unknown powers of the unconscious mind, democratization of political power and psychology of the crowd as well as the influence of commercial entertainers and the growing presence of women in public spaces.”

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

Mind-reading, telekinesis, hallucination, communication with the dead as well as mesmerism or magnetism—two contemporary terms for hypnotism—and other “psychical” phenomenon were all topics of fascination not only for the general public, but also for those exploring the mysteries of the brain.

In Paris around the same time, Schultheiss recounted, hypnotism was also being debated in a highly publicized court case. A young woman stood accused of murder. Her defense claimed she was the innocent victim of a diabolical mesmerist/lover who hypnotized her into strangling a rich man they could later rob.

A defense witness was called from Nancy, in eastern France, the center of a school of medical thought that held that “hypnotic sleep was not qualitatively different from normal sleep and all people were to one degree or another suggestible,” Schultheiss said. “Normal human susceptibility to hypnotic suggestion was not pathological and in fact could be put to positive use for behavior modification, pain relief and even as a form of anesthesia.”

The accused had been manipulated by a schemer skilled at mesmerization, argued the defense, and should not be held accountable for her actions. The argument failed to sway the court, however.

Citing Charcot, the prosecutor general concluded, “Hypnotism could never overcome an individual’s core convictions or alter her fundamental character and personality. In hypnotic sleep, the will can be stolen, but not abolished.”

The Salpêtrière community was undeterred, Schultheiss noted. “To many doctors, including Charcot, the serious criminal potential of unregulated hypnotism was more hypothetical than real,” she said, “and the more ominous threat was not to law and order, but to public health.”

By the late 1880s, unregulated popular hypnotism was legally prohibited in most of Europe. In France, however, Charcot’s efforts to officially police the practice largely failed.

“The threat presented by hypnotism should, I think, be understood simultaneously as a professional response to a real public health threat, as an expression of anxiety about the powers of the mind that were only beginning to be explored, and by the rapid social, political and cultural changes that marked the last decade of the 19th century,” Schultheiss concluded. “This was the Belle Epoque, but beneath the elegant surface of an affluent, carefree society lay many uncertainties and potential dangers—dangers like nervous weaknesses that could by accident or intention be brought to the fore.”