Cell Transplants Could Treat Chronic Pain Caused by Nerve Damage

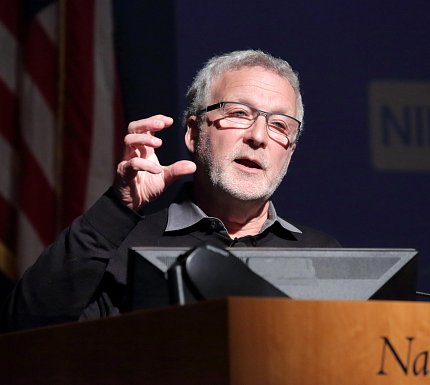

Photo: Ernie Branson

The best treatment for neuropathic pain, that is, chronic pain caused by nerve damage, only works in 30 percent of patients, and at best a 30 percent reduction of pain is typical, said Dr. Allan Basbaum at a recent Wednesday Afternoon Lecture in Masur Auditorium.

“There are a lot of people being under-medicated. They are being treated, but nothing is working, regardless of what they are trying,” said Basbaum, professor and chair in the department of anatomy at the University California, San Francisco. At the lecture, he summarized his efforts to develop alternative treatments.

Neuropathic pain is different from pain that results from other conditions. A patient with arthritis, for instance, might experience pain. That discomfort is caused by inflammation of tissues that surround a person’s joint. If the inflammation can be treated, the pain goes away.

Basbaum defined neuropathic pain as “a disease of the central nervous system.” Nerve damage causes pain. To alleviate it, the nerve damage must be treated. Some conditions associated with neuropathic pain are complex regional pain syndrome, trigeminal neuralgia, stroke, spinal cord injury and multiple sclerosis.

There are several treatments, Basbaum said. Examples include topical anesthetics and anticonvulsants used to treat epilepsy. Opioids are generally not particularly effective for neuropathic pain and there are few studies of the utility of cannabinoids. However, even for the most commonly used approaches, the effects are fleeting and may have serious side effects. Oftentimes, nothing can be done if these treatments fail.

Instead of trying to treat symptoms, Basbaum has been working on a different approach: repairing nerve damage through embryonic nerve cell transplants and, more recently, stem cell treatments.

When there’s nerve damage, the central nervous system processes pain differently. This results, in part, from a decrease in the normal inhibitory control exerted by a population of neurons that use the chemical gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) as its neurotransmitter.

Normally, GABA helps dull the perception of pain. When GABA-expressing neurons are damaged, secondary to the nerve damage, pain doesn’t subside and stimuli that are normally not painful, even light touch, can provoke intense pain. This is what makes the lives of patients with neuropathic pain miserable, Basbaum noted. Patients with neuropathic pain also experience spontaneous pain and “it’s almost always a burning sensation.”

In Basbaum’s laboratory, researchers have been transplanting embryonic nerve precursor cells from the brain’s cortex—cells that give rise to inhibitory nerve cells—into the spinal cord of a mouse model for neuropathic pain. He said neuropathic pain decreased without side effects in mice receiving the stem cell transplants. Dr. Joao Braz, an associate researcher in his lab at UCSF, has performed most of these studies.

Photo: Ernie Branson

Basbaum decided to implant the precursor cells into the spinal cord after several of his colleagues at UCSF showed that cortical precursor nerve cells could be coaxed into developing similarly into GABA neurons in the brain. Importantly, one of their studies was conducted in a mouse model of epilepsy. Basbaum thought he might be able to insert the cells into the spinal cord of a mouse because neuropathic pain and epilepsy are both diseases of a loss of inhibitory control in the central nervous system.

There was no guarantee the experiment would succeed because cortical precursor cells normally develop in the brain; there was no evidence that they could survive in the spinal cord. In fact, the cells did survive and integrated into the neural circuitry of the host spinal cord. And most importantly, the integration was functional and could ameliorate pain hypersensitivity in both a traumatic nerve injury and a chemotherapy-induced model of neuropathic pain.

Basbaum’s laboratory is also transplanting the GABA-ergic precursor cells into the spinal cord of mutant mice with a chronic itch condition, also associated with loss of GABA-ergic neurons in the spinal cord.

While it’s not always thought of as a major clinical problem, chronic itch can be debilitating. Itch can be so severe that some patients actually scratch through skin and bone. Recent results demonstrated that the transplants are, in fact, remarkably effective against chronic itch.

While results from mouse studies are encouraging, Basbaum said it’s still too early to say whether transplants will prove successful in human clinical trials. He is now conducting additional studies in which human embryonic stem cells modified to become GABA-ergic neurons are transplanted into the spinal cord of mice. Results of these studies should be published in the near future.

In closing, Basbaum emphasized that chronic pain is not merely a process by which injury messages are transmitted from the spinal cord to the brain. Rather, “Pain is a complex perception that’s colored by emotions and experience.” For this reason, pain management must consider a blend of pharmacological, psychological and, hopefully in the not too distant future, transplant approaches.

“Every individual who suffers from chronic pain is different, so that a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach to pain management should always be considered,” he concluded.