Confronting Structural Racism

NIH Holds First Town Hall on Achieving Equity

Recognition of a disorder is the first step to fixing it.

From witnessing blatant discrimination of Black patients as a medical student to being unfairly segregated within a county’s public school system to being rejected as a resident physician by a White ER patient, top NIH leaders told personal stories of racism they had experienced firsthand. The message was clear: Structural racism had affected nearly all, even if its harm was obvious to only some.

Instead of shrinking from the problem, NIH now seeks to take the first step and confront it head on.

At an Apr. 30 virtual Town Hall on Achieving Racial Equity, NIH director Dr. Francis Collins introduced the issue of “achieving racial equity at NIH and at the institutions we fund” as one “of paramount importance.” He described the recent social climate in the United States that pushed the need to address racism urgently.

“Nearly a year ago,” Collins recounted, “the murder of George Floyd became one more example of a seemingly endless procession of senseless deaths of Black, African-American, Hispanic and Latino men and women in America. The impact was felt around the world. Recently we’ve also witnessed a disturbing rise in violence against Asians. Furthermore, the ongoing plight of Native Americans in our country cries out for justice.”

In addition, he continued, nationwide, actions and events reflecting bias seemed to have metastasized to target immigrants, people with disabilities, sexual and gender minorities and people in other marginalized groups.

“Structural racism—let’s name it—persists, despite decades of civil rights and other movements to eliminate oppression,” Collins said.

Structural racism is defined as “policies and practices entrenched in established institutions that result in the exclusion or promotion of particular groups,” he said. “Within our own biomedical research enterprise, structural racism limits access to funding, to training and to employment opportunities for far too many underrepresented groups. NIH alone can’t fix more than 400 years of structural racism, but we can do our part with the resources of the world’s largest supporter of biomedical research.”

The town hall was NIH’s first ever to confront racism so directly. Collins said efforts discussed at the meeting “represent our shared commitment to address structural racism within the biomedical research enterprise. Our ultimate goal is to achieve racial equity. That is the condition in which one’s racial identity no longer predicts how one fares. We’re not there yet.”

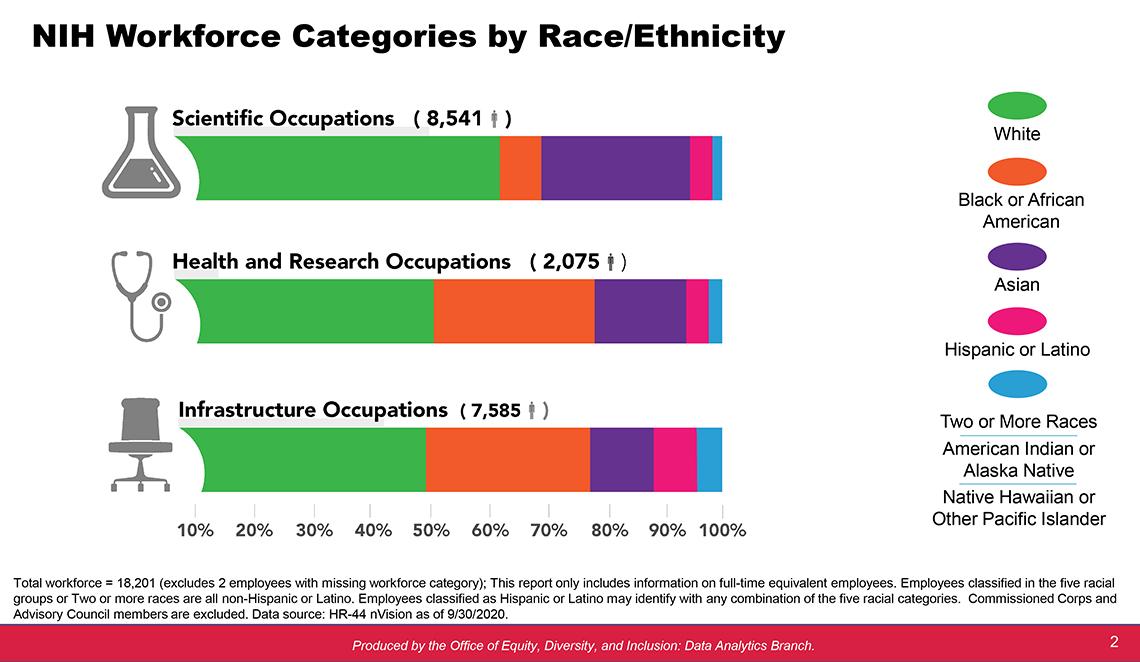

After recounting her experience with racism as a youngster, Treava Hopkins-Laboy, acting director of NIH’s Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, presented workforce data that offered evidence of Collins’s point about NIH’s current position in achieving racial equity. Black, African-American, Hispanic, Latino, and Native American employees are vastly underrepresented in the scientific workforce and administrative positions of power and authority.

“This data is sobering,” she pointed out. “It clearly showcases the racial imbalance that exists at NIH. We are committed to transparency. With the help of the entire workforce, we’re enthusiastic about moving forward with efforts to enhance diversity at NIH.”

Also speaking to the online assembly was NIH principal deputy director Dr. Lawrence Tabak, who talked about candid discussions NIH leadership had with two self-assembled entities—a group of senior, tenured African-American scientists and “8CRE,” a group presenting eight changes for racial equity. He said NIH owes the groups a debt of gratitude for their honesty and courage in sharing their insights.

Reflecting on his own professional journey and lessons from the past year, Tabak said, “What I have learned is that I don’t really understand the insidious nature of a hard-wired system that maintains the status quo.”

He also serves as one of three cochairs of UNITE, a five-committee group consisting of a cross-section of NIH’ers from all 27 institutes and centers that was set up several months ago to guide the agency’s long-term initiative to end structural racism.

UNITE is an acronym for the five target areas and major strategies of the initiative: U-understanding stakeholder experiences through listening and learning; N-new research on health disparities, minority health and health equities; I-improving the NIH culture and structure for equity, inclusion and excellence; T-transparency, communication and accountability with internal and external stakeholders; and E-extramural research ecosystem—changing policy, culture and structure to promote workforce diversity.

UNITE’s other cochairs, NIH deputy director for management Dr. Alfred Johnson and NIA deputy director Marie Bernard, who also serves as NIH acting chief officer for scientific workforce diversity, also talked about experiences with racism from their own lives.

“Although we will not solve all the structural problems that led to these experiences,” Bernard said, discussing the basics of UNITE, “I think we can make significant strides to making NIH the ideal institution where all—regardless of race, ethnicity, sex, gender, abilities, past background—are equally valued and able to contribute to our enterprise.”

Johnson agreed, describing concrete actions the committee is taking already. “UNITE is determined to acknowledge and detail where we are,” he said.

It was the sharing of personal stories that seemed to resonate most with the audience, however. A majority of respondents to a survey after the town hall cited hearing participants’ own experiences as having an impact. Presentation of the NIH workforce data also was noted by respondents as beneficial.

“We are listening to all of you and we are acting,” Collins said, concluding the meeting. “Throughout this process we promise to reflect on our actions. When we make missteps—and we will—we will acknowledge those mistakes and with your help and insight will try to redirect ourselves and act accordingly…Know that this is just the first of many town halls on this topic. Help us to sustain these efforts to dismantle structural racism and achieve our goal of producing equitable power, access, opportunities, treatments and outcomes for all. The consequences of structural, interpersonal and institutional racism are very real.”

More than 7,800 viewers tuned in live, with an additional 700 people watching later, on demand.

Weeks before the virtual meeting, organizers had asked via all-staff email for questions that could be answered during the town hall. Staff submitted 320-plus queries that were grouped into 27 frequently asked themes. Even after categorizing similar questions, only 16 were able to be answered during the hour-long meeting. Collins vowed to provide follow-up via an intranet site under development by UNITE.

Listening sessions and other smaller-group opportunities for dialogue on racial issues are also being planned.

NIH employees are urged to view the town hall, which is archived at https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=41953.