Squishy Sea Creatures Yield Clues to Aging, Healing

Photo: ANDY BAXEVANIS, NHGRI

NIH researchers uncovered insights into healing and aging by studying how a tiny sea creature regenerates an entire new body from only its mouth.

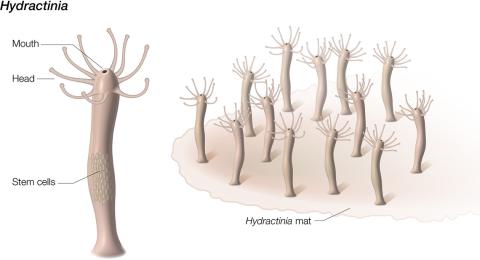

The researchers sequenced RNA from Hydractinia symbiolongicarpus, a small, tube-shaped animal that lives on the shells of hermit crabs. As the Hydractinia were beginning to regenerate new bodies, the researchers detected a molecular signature associated with the biological process of aging, also known as senescence.

According to the study published in Cell Reports, Hydractinia demonstrate that the fundamental biological processes of healing and aging are intertwined.

Humans have some capacity to regenerate, like healing a broken bone or even regrowing a damaged liver. Some other animals, such as salamanders and zebrafish, can replace entire limbs and replenish a variety of organs. However, animals with simple bodies, like Hydractinia, often have the most extreme regenerative abilities, such as growing a whole new body from a tissue fragment.

A regenerative role for senescence stands in contrast to findings in human cells.

“Most studies on senescence are related to chronic inflammation, cancer and age-related diseases,” said Dr. Andy Baxevanis, senior scientist at NHGRI and an author of the study. “Typically, in humans, senescent cells stay senescent, and these cells cause chronic inflammation and induce aging in adjacent cells. From animals like Hydractinia, we can learn about how senescence can be beneficial.”

Photo: ANDY BAXEVANIS, NHGRI

In humans, stem cells mainly act in development, but highly regenerative organisms like Hydractinia use stem cells throughout their lifetimes.

Hydractinia stores its regeneration-driving stem cells in the lower trunk of its body. However, when the researchers remove the mouth—a part far from where the stem cells reside—the mouth grows a new body. Unlike human cells, which are locked in their fates, the adult cells of some highly regenerative organisms can revert into stem cells when the organism is wounded. The researchers therefore theorized that Hydractinia must generate new stem cells and searched for molecular signals directing this process.

The researchers scanned the genome of Hydractinia for sequences like those of senescence-related genes in humans. Of the three genes they identified, one was “turned on” in cells near the site where the animal was cut. When the researchers deleted this gene, the animals’ ability to develop senescent cells was blocked and, without the senescent cells, the animals could not regenerate.

We humans last shared an ancestor with Hydractinia—and its close relatives, jellyfish and corals—over 600 million years ago, and these animals don’t age at all. Therefore, the researchers theorize that regeneration may have been the original function of senescence in the first animals.

Photo: Darryl Leja, NHGRI

“We still don’t understand how senescent cells trigger regeneration or how widespread this process is in the animal kingdom,” said Baxevanis. “Fortunately, by studying some of our most distant animal relatives, we can start to unravel some of the secrets of regeneration and aging—secrets that may ultimately advance the field of regenerative medicine and the study of age-related diseases as well.”