NCI Biologist Invents Safer Pepper Spray

Photo: ALPHASPIRIT.IT / SHUTTERSTOCK

This story is part of an exclusive, ongoing series on NIH makers and inventors.

An NCI scientist has invented a safer pepper spray for use by law enforcement and for personal protection.

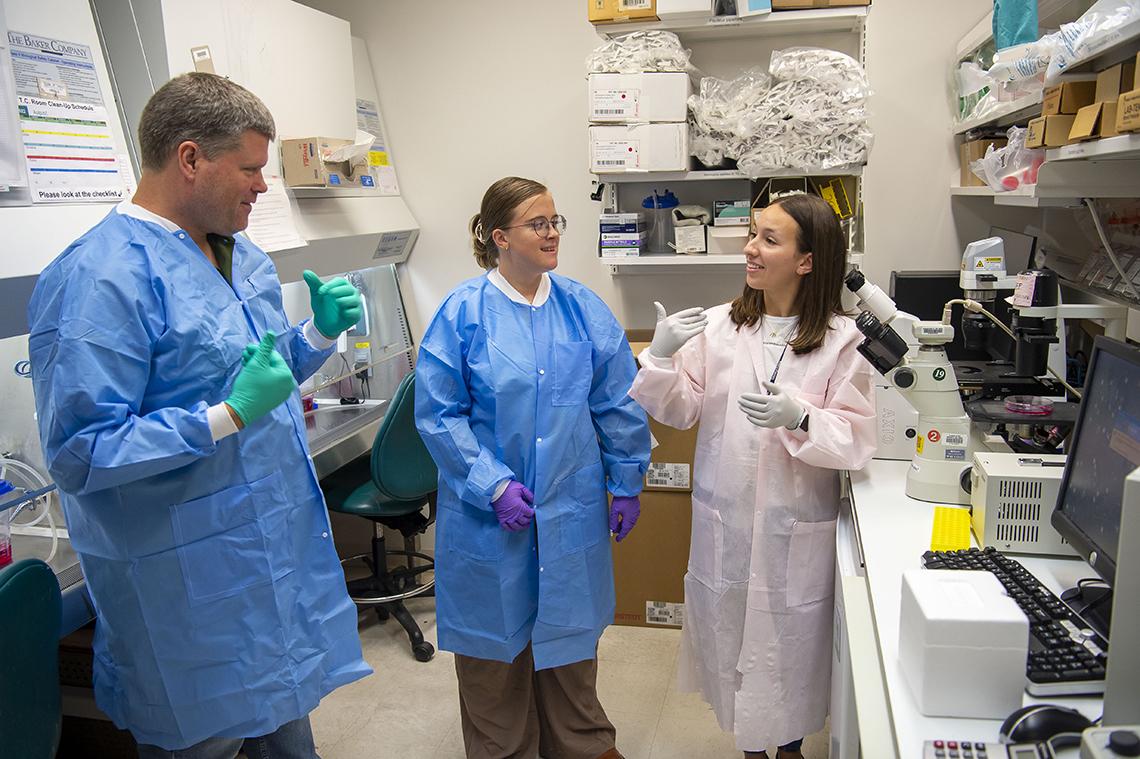

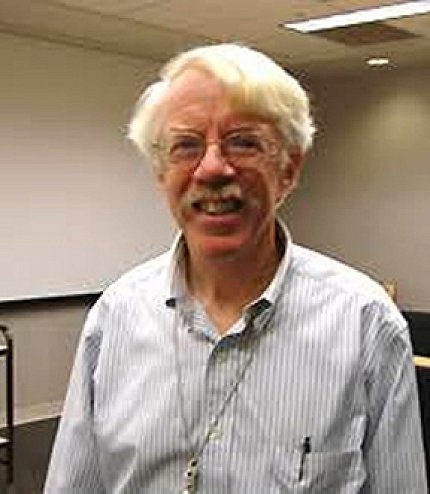

Larry Pearce, a biologist in NCI’s Laboratory of Cancer Biology and Genetics and, his co-inventor, retired NCI investigator Dr. Peter M. Blumberg, developed a pepper spray that, when administered, causes a painful stimulation and incapacitates a person for only a brief period.

“We can now offer a product that works to alleviate pain, but only for a brief period of time, for more effective riot control and other self-defense measures without resulting in a permanent injury,” said Pearce.

Pepper sprays contain capsaicin, a potent chemical irritant. It’s the active component of chili peppers, said Pearce. Capsaicin makes peppers taste hot. The compound has also been used in traditional medicine to alleviate joint and muscle pain.

Current pepper sprays on the market have several drawbacks, he explained. They cause pain for excessively long periods of time and might be life threatening for people who have asthma or hypersensitive airways. In extreme cases, the sprays could lead to permanent blindness, asphyxiation and pulmonary edema.

The NIH inventors added a slow-acting antagonist to counteract the noxious effects of capsaicin to pepper spray. They intended to turn their idea into a manuscript and a patent. They wanted to own a patent that would be useful and, potentially, save lives. This problem seemed to be a natural extension of what he was doing, so something Pearce could also do on the side.

“The idea, of course, was to allow enough time for law enforcement officials, for example, to incapacitate or immobilize the recipient/suspect—normally under 4 minutes—before the effect of capsaicin is suppressed by the slow-acting antagonist,” he explained.

It took Pearce more than six months to identify a suitable compound following a series of in-depth analyses. It had to be non-toxic, have short-enough half-life and a slow-enough response rate independent of capsaicin dose and be commercially available.

The team first applied for a patent on their invention in March 2010. They were assigned a patent a year later with the publication date on Mar. 8, 2016.

A company in Canada licensed the rights from NIH, which holds the rights for inventions made by its employees. (A chili-pepper birdseed that’s squirrel-proof is another invention from that group that has been licensed.)

“Peter and I also thought about doing a species-specific pepper spray,” such as dog repellant for postal workers, and deer and rabbit sprays to protect crops, he recounted. “But we never got that far.”

Pearce started his career at NIH in 2003 as a postbaccalaureate in Blumberg’s lab after he graduated from Gallaudet University with a biology degree. There, the postbac studied capsaicin and its effects on cancer cells. The researchers demonstrated that therapeutic doses of capsaicin can induce apoptosis, or the process of programmed cell death, in several types of cancer cells, including colon, pancreatic and prostate. Capsaicin appears to have a deleterious effect on dysfunctional mitochondria, but it also seems to play a role in the production of new mitochondria, also known as mitochondrial biogenesis.

His more than 50 publications represent cutting-edge contributions to the understanding of the pharmacology of the capsaicin receptor, TRPV1, an area the importance of which was highlighted by the 2021 Nobel Prize to David Julius.

In certain conditions, capsaicin can also induce autophagy to prevent the proliferation and continued survival of senescent cells, which can no longer divide, but continue to function. Autophagy is the process by which a cell breaks down and destroys old, damaged or abnormal proteins and other substances in its cytoplasm.

Remarkably, only cancerous cells appear to be susceptible to the apoptotic effects of capsaicin. “We still aren’t sure why that is,” he said.

Pearce shifted his focus to cancer metastasis after he moved to Dr. Kent Hunter’s lab following Blumberg’s retirement in 2018. While he no longer studies it, “I still find research on capsaicin to be fascinating. I look forward to learning about new discoveries and advances in the field!”