One Step Closer

Hammoud, Swenson Develop New PET Tracer for Fungal Infections

This story is part of our ongoing series on NIH intramural makers and inventors.

Nothing worth having comes easy.

Two NIH makers, Dr. Dima Hammoud and Dr. Rolf Swenson, are quite familiar with that adage. It took them almost five years of trial and error to develop a brand-new imaging method that will allow doctors to rapidly and accurately diagnose invasive fungal infections.

At least 1.6 million people globally die from fungal infections each year, a mortality rate surpassing that of tuberculosis, malaria, hepatitis and pneumonia. But diagnosing some of these fungal infections can be tricky because the available diagnostic methods are insensitive, nonspecific and/or invasive.

Immunocompromised patients are especially susceptible to fungal infections, and consequences may be fatal. Antifungal drugs can also have significant side effects, so doctors tend to avoid giving them before they confirm the type of infection. Confirming a fungal infection, however, is invasive and time-consuming. Clinicians need a faster, easier way to diagnose them. Realizing the urgent need for a noninvasive fungal-specific imaging tracer, Hammoud and her team decided to develop a fungal-specific PET ligand.

“This [invention] was born from a need,” Hammoud said. “Multiple patients who are successfully treated with chemotherapy and/or transplant end up succumbing to fungal infections because of their immunocompromised states.”

As a senior investigator and radiologist with the Radiology and Imaging Sciences department at the NIH Clinical Center (CC), Hammoud often relies on structural imaging like computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to make diagnoses. However, she noted, while she can identify a lesion on a patient’s brain or lungs using CT or MRI, it’s often difficult to pinpoint the actual cause—is it a tumor, an infection, inflammation? If it’s an infection, what kind?

In her lab, Hammoud mostly relies on positron emission tomography (PET), a technique which uses special molecules called ligands carrying radioactive tags—positron-emitting isotopes—to visualize certain tissues or processes of interest. Hammoud uses PET imaging mainly to better understand how certain infectious diseases affect different organs and interact with the immune system.

To develop a fungal-specific ligand, Hammoud and her team exploited already existing fungal metabolic processes. They set out to develop radioactively tagged versions of certain molecules, mainly sugars, that are known to be used by fungi only. The idea is that when the fungus encounters those tagged sugars, it incorporates them, producing a radioactive signal on PET scan and confirming the presence of the fungus.

Hammoud and her team originally identified two promising sugars for this work: rhamnose and cellobiose. Working with Swenson, a synthetic organic chemist with NIH’s National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Chemistry and Synthesis Center, and his team, the group labeled the molecules Hammoud identified with special PET isotopes so they can be tested in different infections.

The road to discovery was not straightforward, however. Their project, which began in 2019, encountered many obstacles right from the beginning. Developing the animal models, spearheaded by staff scientist Dr. Swati Shah from Hammoud’s lab, was very tedious and required multiple attempts. Logistical issues related to lab space and resources needed to be overcome, and the Covid-19 pandemic caused further delays.

“We decided to start with rhamnose because the chemistry was easier,” Hammoud said. The tagged rhamnose worked well in the lab, but “in mouse models, the fungus wasn’t taking the sugar in sufficient amounts to produce a detectable signal.”

Hammoud, Swenson and their teams persevered, developing and testing multiple versions of tagged rhamnose and other existing ligands for almost two years. Eventually, they shifted their focus to cellobiose.

“It was our next best option,” Hammoud recalled.

“Thankfully,” Swenson said, “each of us wouldn’t let the other give up.”

They began the process again, with Dr. Falguni Basuli, a radiochemist at the Chemistry and Synthesis Center of NHLBI run by Swenson, developing an innovative synthetic method for the tagged cellobiose, and Hammoud and her team testing it first in vitro and eventually in animal models.

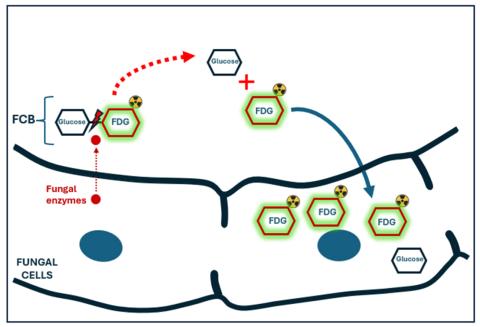

“The idea of cellobiose, which is composed of two glucose molecules bound together, is really cool,” Hammoud elaborated. “In real life, only certain fungi can produce the special enzymes needed to break the bond between the two glucose molecules of cellobiose. Those enzymes are not present in bacteria or in mammalian cells. By adding a radioactive tag to cellobiose and exposing it to fungal infection, such as Aspergillus, the sugar is broken into two molecules which are then taken inside the fungus. This results in accumulation of the radioactive signal in the infection.

“If there is no fungus, on the other hand, cellobiose remains intact and is eventually excreted by the kidneys with no residual radioactive signal in the body.”

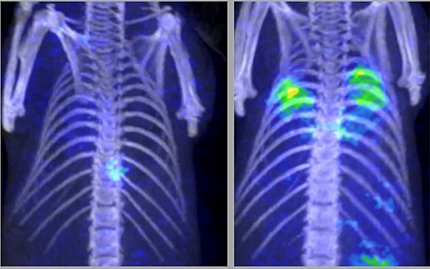

The radiolabeled cellobiose was eventually proven in animal models to be a specific imaging ligand for certain invasive fungi like Aspergillus.

After so many failed attempts with other sugars, when Hammoud and her lab finally saw high radioactive signal localizing to the fungal infection on PET after injecting the tagged cellobiose, they thought it must be a fluke. But it was the breakthrough they were hoping for. She and Swenson published their work in August 2024.

Their next big goal is to test their findings in a human clinical trial. Cellobiose is an approved food additive and is also found in many vegetables but is minimally absorbed from the intestinal tract into the bloodstream. The collaborators are hopeful that it will be well-tolerated by humans.

The hopes of many of Hammoud and Swenson’s colleagues at NIH are also riding on this research. Doctors at NHLBI and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), for example, are excited about the potential for a fungal-specific imaging ligand.

“The reactions of our colleagues in the clinic and their enthusiasm for collaboration make all our effort worthwhile. At the end of the day, we all want to make a difference in the lives of our most vulnerable patients, namely those with weakened immune systems predisposing them to fungal infections,” said Hammoud.

Both researchers repeatedly expressed their gratitude to the NIH intramural research program for providing the opportunity and the necessary expertise needed to carry on this type of high-risk/high-reward research work. Hammoud credited Dr. Cliff Lane of NIAID, founder of the Center for Infectious Disease Imaging (CIDI), former CC director Dr. John Gallin, who passed away in 2024, and all her mentors for believing in her and supporting her efforts.

“They genuinely wanted me to succeed, and did everything they could to make it happen” she said.