Home Alone

Consider Canine Separation Anxiety as You Return on Site

Returning to work on site is an adjustment for everyone, but have you considered how your furry friends will handle the change? Roughly 20 percent of dogs experienced separation anxiety pre-pandemic and vets estimate that number to be higher now that people are returning to in-person work.

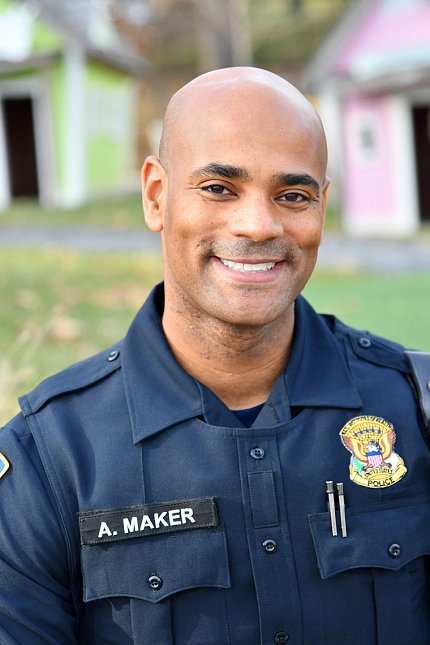

How can you make your return easier on your dog? NIH Police Sergeant Alvin Maker and veterinarian Dr. Meghan Connolly from the Division of Veterinary Resources weighed in during a recent NIH Employee Wellness Seminar titled “Preventing Canine Separation Anxiety.” The lecture was so popular, it was given twice.

Maker is a skilled dog trainer, holding certifications from the Victoria Stillwell Academy, American Red Cross for Dog First Aid and CPR and PetSmart dog training. He also has volunteered at the ASPCA of Anne Arundel County and currently is an adjunct faculty member at the Community College of Baltimore County, specializing in dog obedience training.

Connolly received her degree from the University College Dublin School of Veterinary Medicine. She completed a residency in laboratory animal medicine at Yale University and is currently pursuing a second specialty in animal behavior through the American College of Veterinary Behaviorists.

“Dogs with separation anxiety experience distress when home alone or…separated from their family members,” Connolly explained. This can occur even if the dog is in a different room or blocked off by a barrier such as a baby gate.

Separation anxiety may be especially common for so-called “pandemic pets,” or animals that were adopted during the pandemic and grew accustomed to their family members being home for extended periods of time.

Separation anxiety may manifest in clear signs of distress such as whining, shaking and panting. Dogs with this condition may also show destructive behavior like chewing on furniture or relieving themselves indoors. Rescue dogs or those who have changed homes multiple times may be more prone to anxious behavior, Maker said, but human behavior also plays a significant role in molding canine conduct.

“Making a big fuss over your dog when you’re coming or going [from the house]” can function as a reward for overexcited behavior, Maker said. “Dogs are very connected to human emotion.”

Canine Conditioning

This behavior-reward exchange is also an example of operant conditioning. The core foundation of dog training utilizes two types of conditioning: operant and classical.

In operant conditioning, a learner associates a voluntary behavior with a consequence (positive, negative or neutral). Maker provided the example of his dog Jax, whose adorable begging face will sometimes earn him a bite of Maker’s dinner. Begging is a voluntary behavior, and table scraps are a positive consequence. Jax (along with many other cute pups) has learned to associate begging with a food reward.

Classical conditioning is the association of a stimulus with an involuntary response. One famous example is physiologist Ivan Pavlov’s experiment with dogs in which he observed that dogs would salivate in response to a sound when that sound had been paired with a food reward.

“What are some things [you do with] your dog that might classify as classical conditioning?” Maker asked viewers. This can qualify as both intentional and unintentional behavior on the part of the human.

Training is a form of intentional classical conditioning. In clicker training, the dog learns to associate the sound of a “clicker” device with praise. You can also use a visual signal if your dog is deaf or hard of hearing.

What’s an example of unintentional classical conditioning? It could be your morning routine before you leave for work. “Whatever you’re bringing with you [to work] on a regular basis…are signs or cues or markers that you’re about to leave the household,” Maker explained. Dogs notice this pattern of behavior and it may be enough to trigger anxiety for your furry friend.

Knowledge is Power

Photo: Amber Snyder

So, now that you know what may be causing stress in your dog’s life, how can you prevent or reduce separation anxiety?

Maker reminded viewers to leave and enter the house calmly. You can also “reprogram” certain triggers that you may have unintentionally taught your dog. “Put on your coat, grab your keys [and] go to the living room and watch TV,” he advised. This tweak to your routine can help your dog learn that this set of actions doesn’t always mean that they are going to be left alone.

Training beyond this “reprogramming” can also be beneficial to your dog. Maker set out a checklist for dog owners: identify the problem (i.e., excessive barking), set a goal (reduce barking), change the situation (don’t have the dog in view of the mail carrier) and train for different results. You should also be sure to rule out any underlying health issues that could be causing unwanted behavior.

When trying to curb separation anxiety, a good technique is “independence building,” to help your dog learn to be separate from you. Maker teaches this as a sit/stay or down/stay that progresses to the owner being able to leave the room and eventually the house. He recommends using a clicker or a verbal cue such as “yes” or “good” to let the dog know that it has done what you want.

A dog may not know what a clicker means if it has never been trained with one before, but you can “load” the device by clicking it and giving the dog a treat every time he/she looks at you. Eventually, Maker said, the clicker will come to mean: “the behavior you just did was good, so repeat that,” and you won’t need to reward with a treat every time. If your dog is not food-motivated, you can also use a favorite toy as a reward, or even just verbal praise.

Gadgets and Gizmos

With training, your dog can learn to be comfortable being away from you. Maker also recommended regular exercise such as walks or even playing fetch on the stairs if the weather is poor to work off excess energy. Puzzle toys or other playthings that can have food hidden inside can also be good ways to occupy your pet when you are away.

“It’s very important that we exercise our dogs not only physically, but [also] mentally,” Maker emphasized.

Another gadget that he recommends is a “pet cam,” or a camera that connects to your phone so that you can observe your dog remotely. It can be used when you are simply in another room and want to observe your dog while you are practicing the “stay” command, or you can use it to check in on your pet throughout the day while you are at work.

An ideal pet cam has the ability to swivel 360 degrees and should be placed in a room where your dog likes to hang out while you are gone.

Ultimately, Maker said, the goal of the training should be to make your dog realize “they can be in a different space from you and it can be rewarding…They can be comfortable and confident both with you and apart [from you].”

Archived lectures can be viewed at: https://wellnessatnih.ors.od.nih.gov/Pages/default.aspx.

For more resources on training your dog, visit: https://yourdogsfriend.org/.