NIH Research Festival Showcases Innovative Science

Exploring the NIH Research Festival

It’s the premier event of NIH’s Intramural Research Program. As in years past, the 2024 NIH Research Festival spanned several days, featuring lectures, workshops, poster sessions, a vendor expo and a green labs fair.

This year though another event snuck in: a lecture featuring an extramural researcher. It was a first. But organizers concurred that Dr. Manu Prakash’s topic—a low-cost scientific innovation that’s gone global—captured the spirit of the festival.

Read on about Prakash’s invention and another signature talk: Dr. Stephen Whitehead’s efforts to develop a dengue vaccine. They are among the many NIH-funded innovations changing the world.

Frugal Science Can Change the World

By Eric Bock

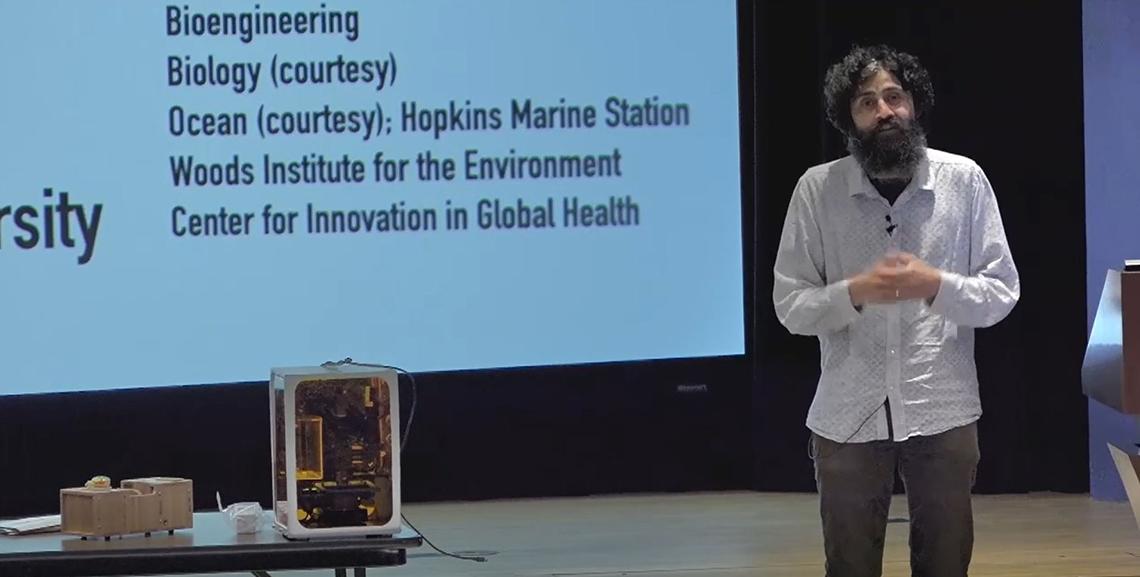

Curiosity is the seed of all science, said Dr. Manu Prakash during a recent Wednesday Afternoon Lecture in Masur Auditorium.

“It’s important for us, as scientists, to think about how to share that sense of curiosity we all experience and practice with the broadest sets of communities,” said Prakash, associate professor of bioengineering, senior fellow at the Woods Institute for the Environment and associate professor, by courtesy, of Oceans and Biology at Stanford University.

His curiosity has taken him around the world. During one of his most recent expeditions, Prakash spent 35 days at sea. While there, he sampled 150 million liters of water.

“It’s a lot of water, but it’s still a drop in the ocean,” Prakash said. And from those millions of liters, he found one single cell that’s only been seen once, back in 1898. These expeditions illustrate how little scientists really know once they step outside the lab.

One challenge to expanding a curiosity-driven approach to science is that many parts of the world don’t have access to health care and education. Some communities in Madagascar, for instance, are a 12-hour walk from their nearest health clinic. Educational opportunities for children in developing countries are also limited.

“Unless technical tools and technologies reach these communities, we might never tackle these sets of problems,” he said.

Prakash’s solution to these challenges is what he calls “frugal science,” or the practice of using creative methods to achieve scientific goals with limited resources. His lab invents, builds and scales up medical devices as cheaply as possible so amateur and professional scientists can work together.

“I believe we can and have, as a humanity, the capacity to dramatically change the course of our trajectories,” he said.

Before starting a new project, he always thinks about how to build access into its design. From his experiences of working in the field, he’s learned, “it’s very important to understand the context and the sets of challenges and problems.” Many of the tools he’s designed have been inspired by feedback he received from people who have firsthand knowledge of problems, such as community health workers.

There are many devices Prakash’s lab could invent. However, the infrastructure to manufacture these devices at scale doesn’t exist in many parts of the world. Manufacturing pipelines must be built from scratch. Recently, they partnered with an airplane engine manufacturer in India to make medical devices.

“They had never touched a medical device before, but I knew they had the capacity because they were already making a sophisticated device,” he said.

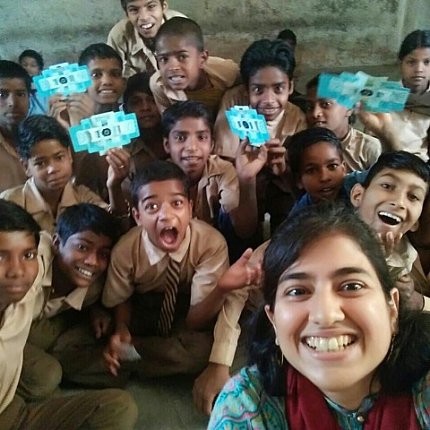

A decade ago, Prakash co-invented a paper microscope called a Foldscope that could be manufactured for less than one dollar. This light microscope has a standard magnification of 140x. He then shipped 100,000 Foldscopes around the world.

With this invention, Prakash created a network of amateur scientists from more than 150 countries. Today, more than 2.5 million Foldscope users share what they discover on Microcosmos, Foldscope’s online community. They can study organisms that Prakash would never have access to. Roughly 700 papers have been published using data collected from Foldscopes.

Photo: Foldscope

“One of the things I’ve been thinking a lot about is how do we translate the principles we learned using this approach to other products,” he said.

For example, he is trying to increase access to diagnostic services, particularly since much of the world doesn’t have access to them. Diagnostic services are vital for the prevention, screening, diagnosis, case management, monitoring and treatment of diseases. His lab is currently working on creating a factory in a small box to manufacture diagnostic tests. They have also created a molecular test that only needs hot water to function.

“We like to joke that if you can make a cup of tea, you can do diagnostics,” he said.

Malaria is one of the most severe public health problems worldwide. Spread by certain types of mosquitos, it is one of the leading causes of death in developing countries. And yet, “surveillance systems for mosquitos are just absolutely abysmal,” Prakash said. His lab developed an app that can quickly identify the species of a mosquito by its buzzing sound.

Photo: Foldscope

Health workers typically diagnose the disease using a microscopic examination of blood film, a time-consuming process. His lab has devised an alternative method to detecting the disease. They developed Octopi, a low-cost and reconfigurable autonomous microscopy platform capable of automated slide scanning and correlated bright-field and fluorescence imaging. Using machine learning, Octopi can analyze blood samples 120-times faster than a traditional microscope.

“We have so many of these instruments in the field now,” he said. “We’re starting to collect the largest digital malaria database.”

Working with people from all over the world has given Prakash insights he would never have had if he worked alone.

“If you have the chance to engage with broader sets of communities, please do,” he concluded.

The full talk is available to view at https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=55005.