A Sense of Importance

Levy Discusses Smell as a Diagnostic Tool

Many people stop to smell the roses, but what happens when we can no longer physically smell the roses? Loss of smell is a common, self-reported symptom that too often gets overlooked in the medical field, yet it can sometimes indicate a more serious health problem.

Loss of smell is a symptom associated with dozens of diseases, said Dr. Joshua Levy, clinical director of NIH’s National Institute of Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), and co-director, the National Smell and Taste Center. He discussed the impact of smell on health at a recent Beyond the Lab speaker series talk.

The ability to smell is critical for safety, nutrition, quality of life and overall health. It can warn us of danger—such as from smoke or fumes or spoiled food. Smell loss can affect taste, appetite and eating habits, which subsequently can lead to nutritional deficiencies. There’s an emotional connection as well. Chronic smell loss is closely associated with depression, anxiety and social isolation.

What’s more, noted Levy, loss of smell is a biomarker for more than 130 diseases and disorders—from viral infections to neurodegenerative disorders.

Levy, a sinus surgeon, offered real-world examples of the importance of smell, sharing patient stories from his practice in Atlanta, where he worked prior to coming to NIH. In April 2020, he said, a healthy woman came in complaining of a loss of smell with no other viral symptoms.

Photo: Dana Talesnik

“As a field, we hadn’t fundamentally connected the dots” that smell loss was a defining symptom of Covid-19, Levy said. “The rest of that story is history.”

In fact, he said, following a viral infection, “self-reported change in smell is not only an early sign, it’s actually more predictive than a fever.”

In another case, a 70-year-old man reported a declining sense of smell for two years. It could’ve been normal. Smell tends to decline with age. But four years later, the man developed a tremor and had difficulty speaking. He had Parkinson’s disease.

This case illustrates the opportunity to test and diagnose Parkinson’s earlier, before the neurologic symptoms develop. Nearly 90% of Parkinson’s patients experience smell loss years prior to developing classic motor symptoms, Levy said. In Alzheimer’s disease, even early on when cognitive impairments are mild, the majority of patients report a diminished sense of smell.

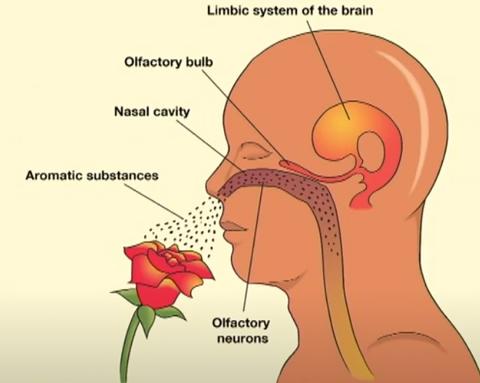

When sense of smell works, that sweet (or foul) smell arrives at the nose through chemicals—or, odorants—that we breathe in. In the nose, there’s a structure called the olfactory epithelium. The receptors there bind the specific odorants that allow us to distinguish the smell.

From there, the signaling moves to the olfactory bulb up to the brain and to the central nervous system. In the brain, the smell travels through olfactory pathways that include the limbic system, the home of emotion. This helps explain why there can be such strong memory components associated with the sense of smell, noted Levy.

Inside the olfactory epithelium, there are millions of receptors capable of detecting thousands of different odorants. But there are not unique receptors for every odor we smell, explained Levy. Rather, each odorant activates several—sometimes dozens—of receptors, which tell the brain what you’re smelling.

Each neuron has the receptor for one specific odorant. “That’s important because we believe that one-to-one relationship is disrupted in other forms of disease,” he said.

An example of this is a qualitative smell dysfunction called parosmia that can develop after recovering from a viral infection.

“The prevalence of qualitative smell disorders has dramatically increased over the last five years,” Levy said, and is a defining symptom in patients with Long Covid.

People with parosmia develop strongly negative perceptions when exposed to a common triggering odor such as shampoo or coffee.

“Imagine waking up one morning to have your favorite cup of coffee but it [suddenly] smells like sewage,” Levy said. “Not only that, it has triggered a panic attack and you have to remove yourself from the room.”

Treatment for parosmia is limited to supportive care. A new clinical trial, launched by NIH’s Smell and Taste Center, is recruiting 80 volunteers to investigate the cause and potentially identify therapeutic targets for future studies.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

“We believe [parosmia occurs due to] a miswiring where that one olfactory sensory neuron, maybe because of recovery from viral injury, no longer attaches to the right glomerulus [structure in the olfactory bulb],” Levy hypothesized. “There’s a mix-up in the code and [therefore] in the perception of the smell.”

Thanks to research by NIH postdoc Dr. Akshita Joshi, it’s now clear that, with parosmia, the brain structurally changes. There’s reduced volume of the olfactory bulb, atrophy of cortical regions and reduced connectivity in the pathways through which the brain interprets smell.

“We know that smell is directly connected to memory and emotion, critical for detecting environmental hazards, essential for flavor perception and nutrition, and an emerging biomarker for neurologic health,” summarized Levy. So why doesn’t it get more attention?

There’s a lack of understanding and training in the medical community, said Levy. Sense of smell can be a remote warning sign but doctors either aren’t making the connection or are outright ignoring smell as a symptom.

Levy emphasized the need to pay closer attention to loss of smell. “There’s a big disconnect in how we’re communicating—how we’re teaching both each other as clinicians and scientists and—with our patients,” he said. “We need to do better.”