For All Ages

Expert Gets Us Talking About the Generations

“I’ll bring in new ideas,” thinks the fresh-faced Generation Z employee. “I know best. I’ve been doing this job for 30 years,” mutters the baby boomer. “Yeah, that’s the problem,” thinks the millennial.

Multiple generations are showing up at work, each with different experiences, mindsets and aspirations. At times, the tension is palpable in office interactions and may be expressed in subtle or overt ways, from unconscious bias to not-so-silent judgment—the eye rolls, sighs, teeth-gritting anxiety, even outright dismissing others’ opinions. Such interactions can leave each generation feeling misunderstood, unappreciated and frustrated.

“Consciously or unconsciously, we do little things that create generation gaps with each other,” said Lynne Lancaster, generation expert, management consultant and author.

Lancaster, who has interviewed thousands of workers from each age group, recently delivered an insightful Deputy Director for Management lecture to help reduce the generational divide.

Everyone wants to believe they like all the generations, she said, but the reality is different. There’s the old-fashioned traditionalist boss who wants everything printed from the internet to the Gen Zer’s puzzlement. Or, there’s the baby boomer boss pestered by frequent questions from her millennial employee. She wants a self-sufficient worker; he simply wants more feedback to do the best possible job.

“If we don’t communicate, we can drive each other nuts,” said Lancaster, who offered tips toward bridging the gaps.

On an organizational level, enhance recruitment and retention strategies. Recruit from a diverse pool and think outside the box, she advised. Is there a younger person ready to step up? Can a bored baby boomer move laterally to a more fulfilling role? Candidly discuss challenges and goals to help cement relationships and retain the best employees.

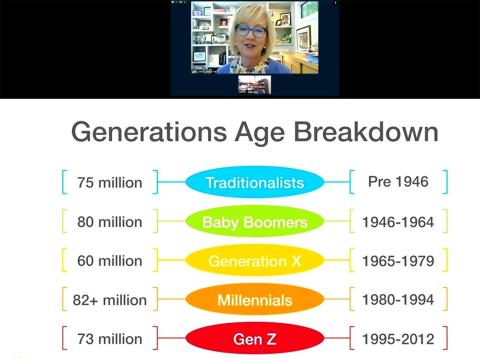

NIH employees are skewing older, said Lancaster, who researched stats before her lecture. As of January, NIH comprises 1 percent traditionalists (born before 1946); 28 percent baby boomers (born 1946-1964 and also close to retirement); 42 percent Gen Xers (born 1965-1979); 27 percent millennials (born 1980-1994) and 2 percent Gen Zers (born 1995-2012).

“You’re going to have a lot of people moving up and out and you’ll want to make sure you have the bench strength to replace them as they go,” she said.

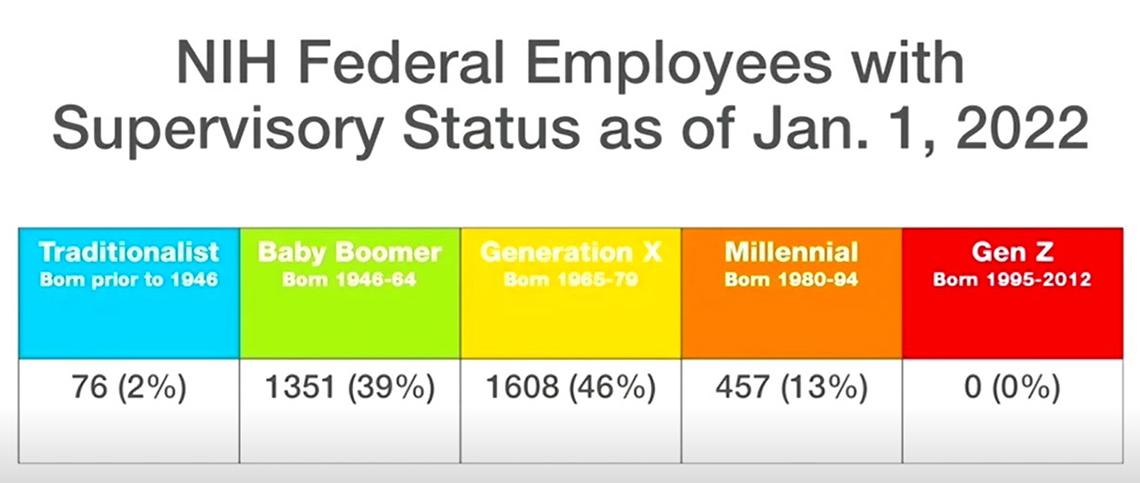

The same goes for supervisory status. At NIH, 39 percent of supervisors are baby boomers and 46 percent are Gen Xers; only 13 percent are millennials. “You must consider,” she said, “are we grooming people for next steps?”

Beyond opportunities for mobility, employees want to feel connected. On an interpersonal level, she said, explore ways big and small to foster a sense of belonging. Does everyone feel comfortable speaking up in meetings? Does someone need more coaching?

“Any generation can feel left out or invisible,” Lancaster said. “The small ways of being inclusive, even just making eye contact, can help make that connection.”

To help reduce misunderstandings among the generations, remember the difference between intent and impact. Something said in the spirit of camaraderie (intent) may get interpreted differently by someone else (impact).

A great example came during the Q&A. An NIH’er said she gets frustrated every time senior leaders call the organization a family; to her, that implies they’re the parents and everyone else is a child.

“An older person meant ‘We have each other’s backs’ and probably never thought family could be a loaded word,” Lancaster responded. “Step back, think what the other person means and give him or her a little grace.” At the same time, respectfully share concerns. Make others aware if a term has negative connotations to you. “We just can’t hear the world through everybody else’s ears.”

One common thread across all age groups is stress, though the causes usually differ among the generations—from health or financial concerns to caring for dependents. Show compassion; support each other.

One stress-causing rift at work is: “Everyone should work just like me!” Undo that notion by appreciating where each age group is coming from.

“Each generation arrives into a world of work that’s different from the last one,” said Lancaster.

“I don’t know what we would have done [throughout the pandemic] if we didn’t have all five generations [here], with their vast amount of experience, skills, history, technology and institutional knowledge.”

—NIMHD executive officer Kimberly Allen

- Baby boomers are fiercely competitive. They had to compete for that first job and next promotion, so they protect their turf and expect younger generations to pay their dues and stay in their jobs longer too.

- Generation Xers, the first generation to emerge from school with tech skills, benefited from a decade-long economic boom that kept hiring them. “Because Gen Xers became this highly valuable commodity, they were able to begin putting pressure on the workplace,” said Lancaster. They’re the first generation to fight for work-life balance—flexible hours, casual Fridays. They’re also skeptical, having grown up inundated with TV commercials in an era of political and corporate indictments. They want to know their organization has their back and will invest in their development.

- Millennials carry the stereotype of the entitled generation but they’re survivors, said Lancaster. They’ve already experienced three major recessions in their lifetime. Despite this, they are optimistic and look for meaningful work. “It’s so important when we manage millennials that they understand the difference they’re making,” she said. And remember, they’re not kids anymore; millennials are now between 28 and 42 years old.

- Generation Z is new to the work world, arriving with tech and everything else changing rapidly and having grown up surrounded by social media. “We need to tap into Gen Z to find more ways we can operate effectively in this global, social environment,” she said. “They’ll lead the way.” Gen Zers want everything to be customizable, from their job duties to their schedules.

To navigate this changing landscape, Lancaster advised setting realistic expectations and managing to goals, not to face time or “butts in a chair.” Be flexible and delegate more authority. “That’s how we build bench strength, how we get better as leaders,” she said, “and it’s how people learn.”

Appreciate what each group contributes. “I don’t know what we would have done [throughout the pandemic] if we didn’t have all five generations [here], with their vast amount of experience, skills, history, technology and institutional knowledge,” said NIMHD executive officer Kimberly Allen.

“What I’ve learned from interviewing people is we all want the same thing,” concluded Lancaster. “Everybody wants to show up at work and do some meaningful work that they care about with co-workers who they like and trust and have their backs. By getting to know the generations, I hope we can achieve that, because we all bring this array of magic into the work we do.”