All in Their Heads

When Faces Made the Case for Lobotomy

If you were mentally ill back in the late 1930s to late 1950s, doctors might have tried to cure you by drilling a hole in your brain and disconnecting the thalamus from the frontal lobe. They may have been convinced to employ this drastic surgery by eccentric neuroscientist Dr. Walter Freeman, “the world’s greatest proponent and pioneer of lobotomy,” who used portraits as scientific proof of concept.

Why did the medical community back then accept what seems preposterous to us now?

That was the fascinating question in “Scientists’ Mind-Body Problems: Lobotomy, Science and the Digital Humanities,” the 2019 NLM James Cassedy Lecture in the History of Medicine delivered Sept. 19 by Dr. Miriam Posner, assistant professor in the information studies department at UCLA.

Photo: Marleen Van Den Neste

“This whole lecture is the story of different modes of proof coming in and out of fashion,” she said. “We find ourselves now in a time when data and statistics claim an enormous amount of cultural authority. One of the central questions of digital humanities is, what can statistics capture and what kind of meaning eludes these methods?”

In the mid-20th century, lobotomies were commonly practiced “on tens of thousands of mentally ill people,” Posner pointed out. “We now think of lobotomy as an atrocity and rightfully so, but it’s also important to understand how a lot of very smart, educated people could have believed otherwise during the procedure’s prime.”

Posner was compelled to examine the surgery’s history, and Freeman’s career, by a photo—and then more photos and old film clips—that she happened to see. The images—before-and-after close-ups of patient faces—were presented in medical journals and textbooks as proof that partial brain excision succeeded in healing mentally ill people.

“It seemed strange to me that there was a time when people’s affect and expressions could be accepted as medical evidence,” Posner recalled. “How could it be that faces made sense as proof 50 years ago?”

Photo: Marleen Van Den Neste

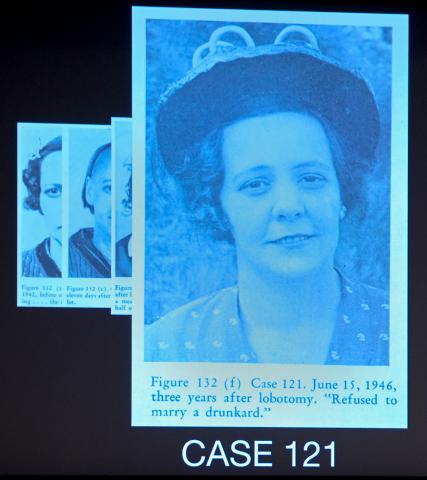

Take Freeman’s case number 121, a woman he photographed several times over the course of some 4 years. In the first portrait, a young woman glares into the camera, unsmiling, brows furrowed. She looks slightly combative. The caption notes, “March 23, 1942 before operation. ‘Forever fighting….the meanest woman.’”

Another image shows the same woman, the top front portion of her hair shorn to the scalp. She’s smiling. The caption reads, “April 4, 1942, eleven days after lobotomy. She giggles a lot.”

By the series’ fifth photo, the woman has donned a contemporary ladies’ hat for her portrait, which was taken 4 years post-lobotomy. Images in between captured her modest weight gain and note that she has found regular employment—both circumstances offered as further “evidence” that lobotomy has benefited her. In picture 5, again she’s smiling. Freeman’s caption: “June 15, 1946, three [sic] years after lobotomy. ‘Refused to marry a drunkard.’”

Photo: Marleen Van Den Neste

By then, 10 years after Freeman had performed the first lobotomy in 1936, the procedure “was very much on the frontlines of medical science,” said Posner. Freeman’s photos illustrated journal articles that he—and many in the medical establishment then—believed were documentation that his surgeries cured severe mental illness.

“Freeman thought psychosis was the result of excessive self-reflection, thoughts that circled back on themselves over and over again,” Posner explained. “He was being literal when he said lobotomy was a way of cutting those endlessly circling thoughts off within the brain, [a way] of breaking that circle.”

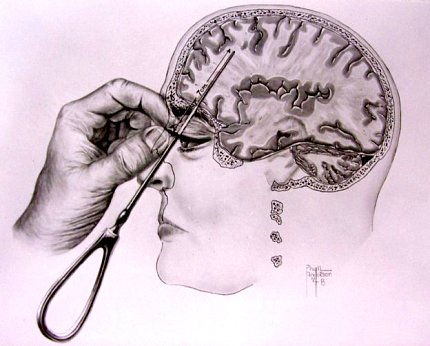

Following Freeman’s lead, hundreds of physicians performed thousands of lobotomies in the United States during the procedure’s prime. By 1945, he had revolutionized the technique. By inserting a long, thin instrument—modeled after an icepick—to pierce the brain via the patient’s eye socket, Freeman devised what he called the “transorbital lobotomy.”

With this invention, he claimed he no longer needed a drill, sterile field nor surgical scrubs. His longtime operating room partner quit in protest. Freeman was undeterred, taking operations on the road by way of a camper van. He traveled the country, performed lobotomies and gave lectures “at an almost frenzied pace,” Posner said.

In a sort of makeshift longitudinal study, Freeman diligently kept a journal, recording his work in words and images, sometimes logging more than two dozen lobotomies in a single day. In a stretch of August 1958 entries, he journeyed from Lincoln, Nebraska, to St. Joseph, Missouri, to Cherokee, and then Independence, Iowa—50 transorbital lobotomies in just more than 4 days across 650 miles of America’s heartland. His new scaled-down method went quicker sans drill, O.R. and surgical assistants.

Only the development of Thorazine as an effective, less invasive anti-psychotic brought the widespread practice of lobotomy to an end, Posner reported. The medical community quickly moved on. Freeman, however, still held that his procedure was better.

So lobotomy fell out of fashion, but in the course of her research, Posner learned there was more to the story of portraits as proof.

“There’s actually a solid foundation for Freeman’s belief that photographs constituted acceptable medical evidence,” she recounted. “He was drawing on centuries of psychiatric and philosophic tradition that saw the face as a legitimate and reliable indicator of the contents of the soul.”

Posner traced the ideology back to 18th century theologian Johann Kasper Lavater, a physiognomy advocate who argued that the face revealed specifics about a person’s character. Some hundred years later, French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot “used photography as a tool of scientific scrutiny.” He gained—and shared—medical insights from having his patients look directly at the camera lens for “the clinical gaze.”

By 1920, Dr. Harvey Cushing was transforming the field of neurosurgery with, among other innovations, his extensive documentation and collection of patient images and brain samples.

“So Freeman’s photographic practice was not as unhinged as it might have seemed at first,” explained Posner. “He actually inherited a long tradition of using faces to demonstrate sanity or insanity.”

Sure, Freeman’s approach to scientific corroboration seemed unorthodox and even shocking when viewed initially, Posner said, but placed in context, our perspective may have changed.

Photo: Marleen Van Den Neste

“When we talk about the history of psychiatry, we have to be careful about which mode of evidence we use to bolster our claim,” she cautioned. “The story the journals tell is different from the psychiatry physicians performed for each other on the lecture stage…The oral performance of medicine could differ markedly from the way medicine is articulated and circulated in medical journals. It’s more theatrical, more improvisational and more visual.”

As 21st century medicine ventures ever farther into the era of Big Data and its widely foretold promise, a history lesson on how scientific evidence is derived, used and communicated to inform treatment strategy seems timely.

“Freeman’s photos suggest to me that for all of 20th century medicine that’s well documented,” Posner concluded, “there are apparently important features of its visual culture that are yet to be excavated.”

Her entire lecture is archived at https://videocast.nih.gov/summary.asp?Live=29010&bhcp=1.